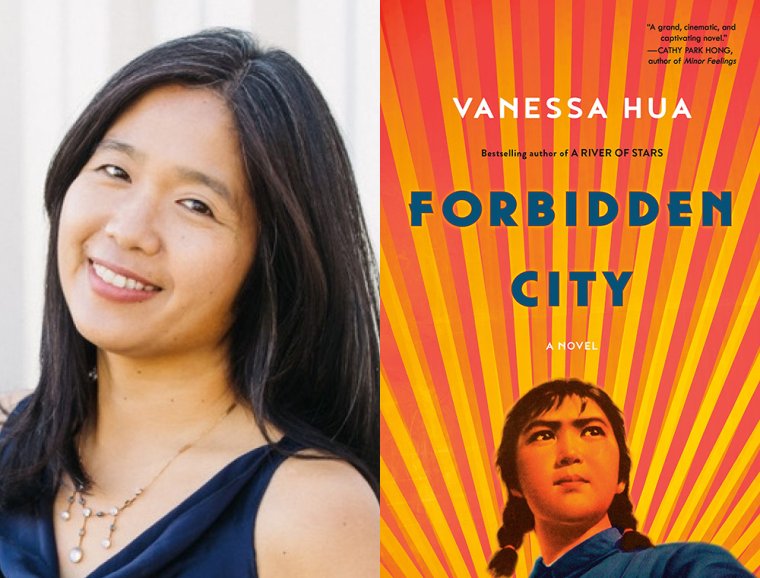

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Vanessa Hua, whose second novel, Forbidden City, is out today from Ballantine Books. In this gripping first-person narrative, the 1976 death of Mao Zedong sparks a street celebration in San Francisco’s Chinatown neighborhood, where painful memories come flooding back to protagonist Mei, who must now reckon with her role in the Cultural Revolution. Readers track Mei’s upward trajectory from naive teenage peasant to Communist revolutionary to favorite acolyte and lover of Zedong himself. When Mei eventually becomes disillusioned amid Zedong’s lies and manipulation, she seeks a way to extract herself from the Chairman’s grasp. Publishers Weekly writes that Hua’s novel “finds a brilliant new perspective on familiar material via its story of a young woman’s brush with power.” Hua’s debut novel, A River of Stars, was released by Ballantine Books in 2019, and Willow Books published her short-fiction collection, Deceit and Other Possibilities, in 2016. A National Endowment for the Arts literature fellow and winner of the Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, among other honors, Hua is a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Vanessa Hua, author of Forbidden City. (Credit: Andria Lo)

1. How long did it take you to write Forbidden City?

I began writing it in 2007, during my MFA program at University of California in Riverside. After I graduated, the novel went out on submission and came close to selling, but did not. Though devastated, I kept writing. I published my short story collection, Deceit and Other Possibilities, and my debut novel, A River of Stars. I couldn’t quit this novel though, and it finally sold in 2016, as part of a two-book deal. I finished final revisions last year. All told, it took about fourteen years, about a third of my life!

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Because it’s set in 1960s China, I did extensive research about Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution, reading scores of books and news stories and conducting interviews. As I wrote, I sometimes got too much into the weeds about political machinations—the minutiae that muddled rather than illuminated the journey of my protagonist.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write in my home office in the East Bay, with a view of a redwood tree and hills beyond, but I also belong to the Writers Grotto, a community with offices in San Francisco. My hours of power are in the morning, when I try to do the work most important to me, but I’ll write whenever my ten-year-old twins are at school or otherwise occupied. I write weekdays and often on the weekend, too. As a journalist, novelist, and creative-writing teacher, I’m always working on a writing-related task—even when I’m away from my desk. In the pool or on a run or walk is where the ideas bubble up from the subconscious, and I consider that time a part of my writing practice, too.

4. What are you reading right now?

Melissa Chadburn’s A Tiny Upward Shove, Vauhini Vara’s The Immortal King Rao, Mecca Jamilah Sullivan’s Big Girl, and Kim Fu’s Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Michael Jaime-Becerra is an amazing author and essayist who writes about the people and landscape of El Monte and the San Gabriel Valley.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I’m a mother who teaches creative writing, writes a weekly column for the San Francisco Chronicle, freelances, and is active in the Bay Area literary community. My time isn’t my own; I have a lot of responsibilities to juggle. Though I’m grateful for these opportunities, I have to remember to preserve and protect the time I spend writing fiction.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

I’m grateful to both my agent and editor, who have helped me become a better storyteller. I always look forward to my editor’s letter and line edits on my novels, carefully penciled in. She’s taught me so much about characterization and finding the heart of the story, but she’s not prescriptive. To prompt a revision, she uses the acronym “OYOW”—“or your own words”—which reflects her trust in me. With her help, I can find a way through.

I also want to give a shout out to my copy editors and cold readers, who pointed out inconsistencies and inadvertent repetition in my novel. For example, I used the verb “gaze” dozens of times. Taking another pass, I realized I could cut many or else substitute another gesture. I use the keystroke control-F to find adverbs and other potential filler to trim, and now I’ll start checking for “gaze” in the future.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Forbidden City, what would you say?

Years ago, I was talking to a writer friend, and we agreed we didn’t need a life coach—we needed a psychic! Someone who could assure us all the rejections and drafts would ultimately lead to publication. Alas, no one can predict the future. If I had known about the twists and turns beforehand, I like to think I would have kept going, but maybe it’s better not to know. I suppose I would tell younger-me—the married journalist without kids—to keep going. To remember the joy, the satisfaction of writing itself, that is separate from publishing and all else out of my control.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I can’t pick just one! My longtime critique partners include authors Yalitza Ferreras, Angie Chuang, Kirstin Chen, and my husband, who isn’t a writer but is an excellent reader. I’m also grateful to the members of various writing groups I’ve belonged to, who’ve read draft after draft.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

My mentor at the University of California in Riverside, Susan Straight, told us to “hook each other up.” To care for each other, to share opportunities, and to go to each other’s readings. To have each other’s backs. Writing is a solitary act, and having a community with whom you can commiserate and celebrate helps you persist.