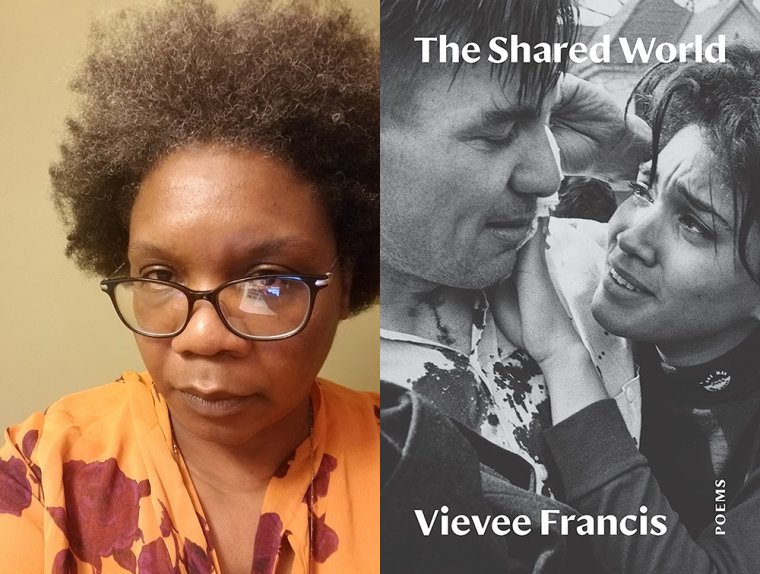

This week’s second installment of Ten Questions features Vievee Francis, whose new poetry collection, The Shared World, is out now from TriQuarterly Books. In these moving poems, Francis explores the dynamics of interpersonal space, the many iterations of human relationship, and how those bonds are shaped or warped by our personal and public histories, media interventions, and identities such as gender, race, and class. Black womanhood is a central point of consideration, and Francis unpacks the ways in which Black women have been particularly constrained by generations of legal, social, and cultural misapprehensions. The collection asks readers to recognize the human mind as a maker and collector of narratives—about ourselves and others—that influence the way we move through and are received by the world. “Into the bow of your ear I whispered the secret story,” Francis writes. “Now you can’t sleep either.” Vievee Francis is the author of Forest Primeval (TriQuarterly Books, 2015), winner of the 2017 Kingsley Tufts Award; Horse in the Dark (Northwestern University Press, 2012), winner of the Cave Canem Northwestern University Press Poetry Prize; and Blue-Tail Fly (Wayne State University Press, 2006). A recipient of a Rona Jaffe Writer’s Award, a Kresge Artist Fellowship, and the Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry, Francis has published poems in numerous print and online journals, textbooks, and anthologies, including Angles of Ascent: A Norton Anthology of Contemporary African American Poetry (2013), Poetry, and The Best American Poetry (Scribner, 2010, 2014, 2017, 2019).

Vievee Francis, author of The Shared World. (Credit: Matthew Olzmann)

1. How long did it take you to write The Shared World?

It took around six years. There are some poems that are much older, which I finally found a home for in this book, but I began writing in a focused way around six years ago, near the time Forest Primeval was released.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

This book feels more expansive to me even as it moves around some concerns I’ve had since my first book, Blue-Tail Fly: the natural world and urbanity, personal history inside of collective History, violence, sensuality, the right to speak without the limitations (constructed/expected) of gender or race, and of course lineage, parity, cost. The Shared World—as with the first book, which is mostly historical persona poems—takes me out of myself, but it does so not by sidestepping my personal/private world but by sharing it within the context of a world we all share. We are all connected by story, by stories it is imperative we, as humans, exchange and acknowledge. I kept losing the balance until I, at last, got as close as my skills allowed. It felt terrifying to open myself up in this particular way. To go back to the South and West that reside in my shaky memories. To at last grieve my mother’s passing. To address my observations of a world wounded by inhumanity and to question my place in such a world. To really note how much I fucking love poets in all of our vulnerability and failure and need and push. To love and hurt so much it sometimes put me into weeks of a kind of catatonia, staring at the page, staring into space day after day, even after the book was done. The challenge was emotional: keeping myself whole while writing the book and overcoming my fear of not having adequately said what I felt needed saying.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I was writing in a lovely writing studio in an old hotel that used to belong to poet and memoirist Cynthia Huntington, but the stairs are now difficult for me to manage so I am not there as often as I’d like. So I spend time, as I always have, in nearby coffeehouses. Hmmm, I may be trying to recreate the coffeehouse culture I loved in Detroit—especially in Hamtramck, Michigan, which is a tiny town entirely within the city of Detroit—like I found at Café 1923. I am constantly asking friends to write near me. The energy of poets feeds me. Unless I am physically unable, or really wrung out, I write everyday. NOT a mandate. Just what I need.

4. What are you reading right now?

Rereading Susanne K. Langer’s Problems of Art: Ten Philosophical Lectures (well, I’m always picking the book up), my husband’s Constellation Route, and Garrett Hongo’s The Perfect Sound: A Memoir in Stereo. I just started Deena Mohamed’s graphic novel (I love graphic novels), Shubeik Lubeik, and just finished Peter Orner’s Still No Word From You: Notes in the Margin and Kathleen Collins’ Whatever Happened to Interracial Love. I’m in the middle of Mark Whitaker’s Saying It Loud: 1966—the Year Black Power Challenged the Civil Rights Movement. I read several books at once because my attention is constantly shifting and I want to see how one text connects, or doesn’t, to another. I’m moving in and out of my colleagues’ texts; I am determined to read all of their books—and that is a lot of reading. On my desks and tables are perhaps more than twenty five books. Like any writer! Monica Youn’s From From. Clint Smith. Kyle Dargan. And on and on. And I am on pins and needles waiting to read Dee Matthews’s Bread and Circus.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

The strategy was loose. The first three poems cover many of the book’s concerns. I take words that symbolize those concerns and move them throughout the text. I revisit and iterate or shift the vantage. It is my way of interrogating myself, my questions, and the world at large.

6. How did you arrive at the title The Shared World for this collection?

The title comes from a Naomi Shihab Nye poem, “Gate A4.”

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of The Shared World?

Heidegger. Specifically, discovering Irene McMullin’s Time and the Shared World: Heidegger on Social Relations, which was published by my press, in its Studies in Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy series! Who knew?

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Shared World, what would you say?

This is funny because I am a great believer in talking to myself to get my head together or figure something out or to just plain comfort myself. I’d say, “Stop being so afraid of your own voice. You want to be inside of the great conversation that is poetry, so speak up.” And the way I speak is to write, then share what I’ve written. You would think after all of this time this art would come easier to me, but it does not. I have to fight for every word, then fight to let them go.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Personal work. Maintaining my physical and mental well-being. My work as a professor. I am a writer who teaches. But I privilege my student’s needs, so I paradoxically had to lean into my teaching so I could then clear a space for my own writing.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

To write where I am, meaning at whatever stage I find myself in, and to write like no one is looking.