This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Will Alexander, whose poetry collection, Divine Blue Light: For John Coltrane, is out today from City Lights Publishers. In this mind-altering volume, Alexander wrangles an array of subjects—including music, painting, literature, quantum physics, and astronomy—to offer a complex meditation on the human mind and spirit. Dedicated to the great jazz saxophonist—whose genius is explored in the title poem “Divine Blue Light: Sudden Ungraspable Nomadics”—the collection is an extended exercise in ekphrasis, with odes not only to Coltrane but a panoply of artistic influences: author Gertrude Bell, poet Fernando Pessoa, and visual artists Joan Miró, Dean Smith, and Chaïm Soutine, among others. In dexterous lines that are less interested in definitive meaning than in evoking states of feeling and consciousness, the poems also function as a critique of English as “lingual aristocracy,” as Alexander puts it in his preface, which his poems resist with their “impalpable lingual blazing.” Publishers Weekly praises Divine Blue Light for its “cosmic energy.... Alexander plumbs language for its limits, often with dazzling results.” Will Alexander is the author of more than two dozen poetry collections, including Refractive Africa: Ballet of the Forgotten (New Directions, 2021), which was a finalist for the 2022 Pulitzer Prize in poetry. He is a recipient of a California Arts Council Fellowship, a PEN/Oakland Josephine Miles Award, a Whiting Foundation fellowship, and the Jackson Poetry Prize from Poets & Writers.

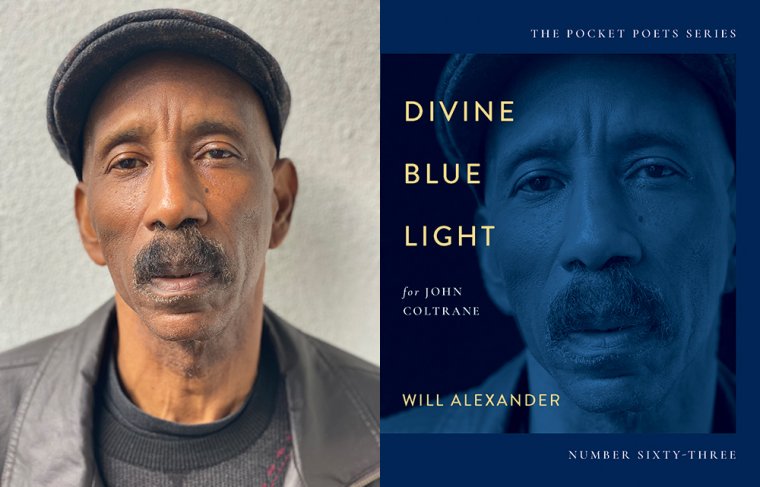

Will Alexander, author of Divine Blue Light: For John Coltrane. (Credit: Sheila Scott-Wilkinson)

1. How long did it take you to write Divine Blue Light?

Within the parameters of the present moment, my arc of creation has seeped into an unclaimable time plane. I don’t sit in an inert posture counting drafts of writing. Rather than foreground isolate particulars, I integrate their energy into the momentum of the larger vision at hand—so that by failing to obtrude they simultaneously extend the larger poetic view at hand. Thereby the particulars extend themselves not by means of some utopian purview but in concert with a larger integrative realm.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I have never had to unlearn the copious swamping that overwhelms the mind according to linear technique. For me the latter reality has always functioned as parallel to poetic obstruction where one quantifies ignition, so that existential lingual broadening fails to concur. The base wilderness was always within me but over time began to alchemically accrue as a principal nexus of development. Because poetic language remains alive within a seeming juncture of generic quotidian ravines, one feels freed beyond juncture commandeered by its generic harassment. Therefore poetic activity is punctuated by the magnetic engulfing of a realm not unlike a phrase enthralled by a wayward imaginary turn of phrase, possibly akin to a phrase not unlike a seeming awkwardness. Its oddness is not unlike a faultless mirage that ignites “a tense or treasonous otter” partaking of an odd or garrulous strategy.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

As Octavio Paz once stated, there exists no tense or strategic time frame. My tendency veers towards simultaneity, not working with some abstract coda via inherent architectural projection as a form of stillborn abstraction but what I would call spontaneous interior alacrity. Not some fact according to poetic conclusion instilled by a state of stillborn abstraction. The poem by its nature remains a pyrotechnics going beyond the plotting within some stillborn ascendant. It remains never a static optical congruent but a possibility in tune with its own aural breathing sans the monarchy that subtends its force according to prior theory.

4. What are you reading right now?

Reading for me can only be existentially integrative. Again, reading a book can never be exquisite or abstract claimed by the goal of knowledge pledged to the monarchy of itself as a form of delimited wisdom. This is not unlike extracting a generic temperature of a partially living relic. For me there exists an exquisite synecdoche. Right now I am working to absorb Gerald Horne’s Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America, which I was fortunate enough to have him sign, and Treasures In Trusted Hands: Negotiating the Future of Colonial Cultural Objects by Jos van Beurden—two of many works that have included writing on “African Fractals.” There is also my ongoing surveillance of contemporary poetry, which includes Carlos Lara, Anthony Seidman, Heller Levinson, and Janice Lee. Not by no means being a conventional scholar, I have by no means attempted to convert the waterfront. As Nathaniel Mackey once related to me, expertise is not an endemic idiom but a state superimposed by others. For a poet, reading exists in its best sense as creative procurement, as organic stimulus. There exists more to say on the topic, but I think one should live it at this stage of openness.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

Divine Blue Light condensed in the manner by which nature coalesces when we gazes at aboriginal foliage as originally gathers as one optimally gathers from the side of a road. This is not to say that Garrett Caples and I surveyed the organics of the original text, never attempting to acquire perfection. At times a stich or two can retain the possibility of creative raggedness, not as a form of obstacle but as evidence that emits a form of creative health. One thinks of Igor Stravinsky or Thelonious Monk never instilled by preset cognitive coherence. I think most organically of perfectionists like Eric Dolphy or John Coltrane never allowing themselves to provoke neediness that obstructs its own power prevailing as superficial perfection. Never chronology that superficially superimposes itself according to chronic denial. I of that which is perceived to be error.

6. How did you arrive at the the title Divine Blue Light for this collection?

My first recognition of title was by the book’s opening title “Condoned to Disappearance,” as it was initially published online. After having the script for a time, it dawned on Garrett Caples that Divine Blue Light condoned the magnetism of the book, and hence so it has stayed. It seemed to possess an organicity that possessed the flexibility of blending organic fiber.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Divine Blue Light?

Never as myopic thirst as superimposed procedure. Instead there was scope of that enthralled by the scope of its spontaneous self-sketching. My association with the realia of Fernando Pessoa’s hetronyms imbued in me a scope that invigoured in me a scope that has always dazzled by its sense of vigor via unforseen possibility. The poems remained alive as unforseen gesture. From the titles themselves and the unforseen nature of the lines themselves, an organic alacrity self-empowered itself within a state that was mesmeric with calm. Therefore the scripting felt organic, as if empowered by the voice of inevitability. It’s as Andre Breton once put it: Lingual consciousness flows with miraculous ease. Not as warped congested fiber, architectural and forcefully misshapen, but a susurrant formation insistently shaping its own power as organic form. Never shape according to force-fed embranglement, but scope that takes shape by its own extended ridding.

8. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

My notion of what Sri Aurobindo shaped through the articulation of the Mother is that when this higher pyschic state arises, a sense of inevitable blueness occurs, not in terms of some painterly palette, but as a spontaneous state that reveals itself not according to cognitive or preplanned effort but according to inevitability that arises from the power of endemic psychic rising. Certainly not a churlish psychological field intellectually conducted according to a conscious state of protracted schism. Not a didactic state that one recalls according to the limitation that conceives its power according to superimposition. Because of this, it is not recall according to prescripted value.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Because I naturally do isometrics on a daily basis, I would listen to John Coltrane’s longest ever solo “One Down, One Up,” recorded at the Half Note in New York City in 1965. Because there feels to be no sense of time within this scope of consciousness, one feels liberated. But what I consider to be mantric protraction. Spell by linear causality evaporates thus liberated presence naturally transpires. Of course this is not a state informed by anything didactic, yet an experience naturally wells from one’s sense of inevitability.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Let your sense of language dawn of its own accord. It should be nurtured not only by reading or one’s power to enter a living alchemical state, not by enduring the written act according to exclusive preplanning. One must function according to the state of one’s natural internal leaning. Not a script as testament to someone else’s leaning, but follow one’s positives, be they feel naturally apt, or fraught by learning through the tenets of one’s seeming confusion.