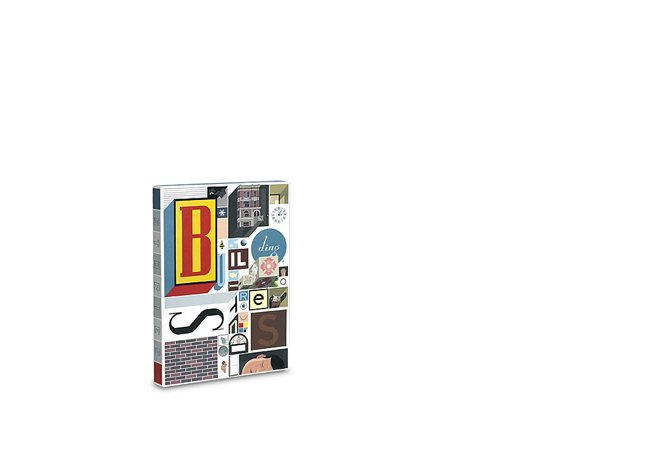

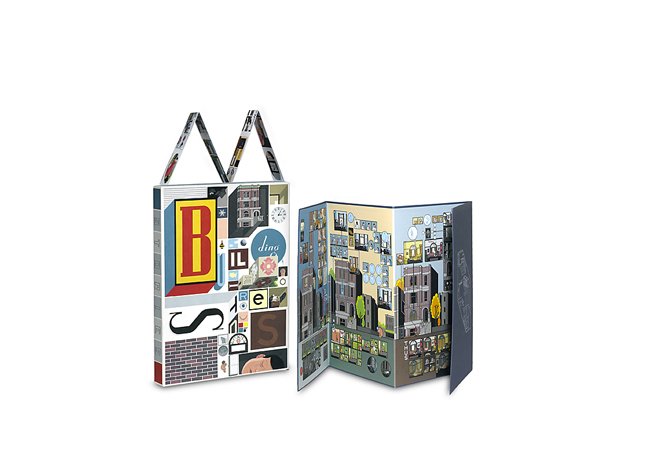

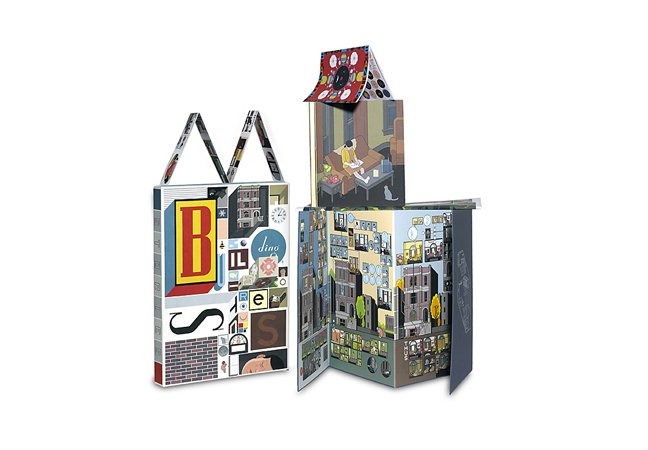

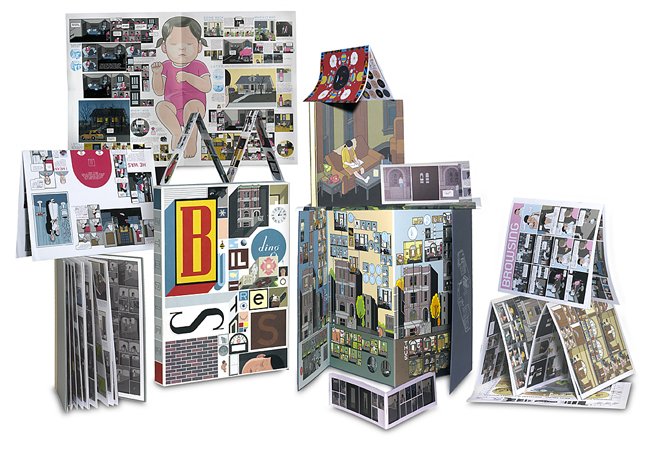

Chris Ware's newest graphic novel, Building Stories, published by Pantheon in October, is actually fourteen discreet books, booklets, magazines, newspapers, and pamphlets, all contained in printed box. More than ten years in the making, the work imagines the inhabitants of a three-story Chicago apartment building, including the protagonist, a thirtysomething woman who has yet to find someone with whom to spend the rest of her life; a couple who can hardly bear to be in each other’s company; and the elderly landlady who has lived alone for decades.

Find details about every creative writing competition—including poetry contests, short story competitions, essay contests, awards for novels, grants for translators, and more—that we’ve published in the Grants & Awards section of Poets & Writers Magazine during the past year. We carefully review the practices and policies of each contest before including it in the Writing Contests database, the most trusted resource for legitimate writing contests available anywhere.