The Gary Paulsen books are in a box in my basement now, yellowing the way all paperbacks do, tucked among the pantheon of the most beloved, the most favorite middle-grade reading experiences I’ve ever had. There are unicorn novels and tales of talking mice fighting fantasy wars, along with the many books about teen wizards. Next to those books stand Paulsen’s, about wolves tearing open the guts of a deer on a frozen lake. Sled dogs running through the night, their toes freezing in an Alaskan winter. Boys learning to build a fire and gut a ruffed grouse. I cherish the books of Gary Paulsen in a different way than the fantasy stories that took me on comforting journeys to fairy tale worlds. The true-to-life pain and fear Paulsen depicted were my first introduction to the brutal honesty a story could contain. His one-word sentences, his hard-hitting and minimalist writing, still stud my memory. I’m grateful to the writer who introduced me to the rough music of the woods, and to writing in a different way, making style stand out. And yet I’m torn: Maybe I loved Paulsen because he represented something that was forbidden to me, because his work represented “masculine” writing, with all its supposed weight and seriousness, those markers of quality that my girlish books—I was told—had not.

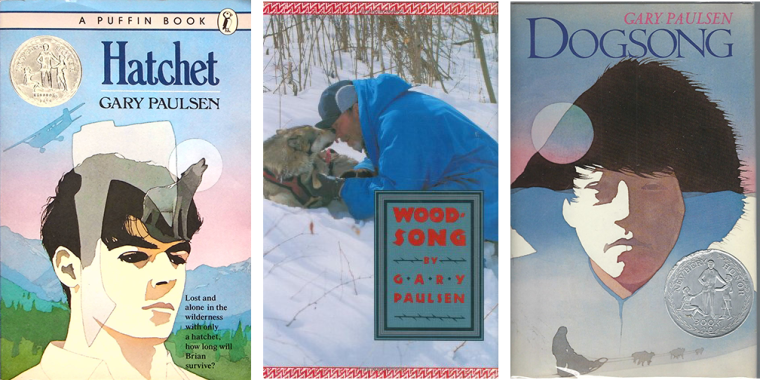

Paulsen, whose works include Hatchet (MacMillan, 1986), Winterdance: The Fine Madness of Running the Iditarod (Harcourt, 1994), and Woodsong (Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing, 1990), and whose accolades include three Newberry Medals, is beloved by generations of young readers. His books are often put in the hands of kids who are reluctant readers, almost exclusively boys. Paulsen’s stories are hard-hitting, direct evocations of survival in different challenging natural environments: dogsledding in Alaska, plane crashes in the remote Canadian wilderness, running with coyotes through deserts, and sailing the open ocean. I listened to many of his books on audio cassette tapes that my mother bought for me, mostly narrated by Peter Coyote, so that the actor’s smoky, hushed voice and Paulsen’s writing are synonymous in my memory. As soon as I discovered a new book, I gobbled it up. Yet once when my father went to the library with me to pick up a Paulsen book, a librarian flatly refused to give them to him: “Those are boy books,” she said. “She won’t like those.”

The genre of “boy books,” with its thin sports biographies and outdated Hardy Boys adventures, has a bleak reputation for quality. Yet somehow these books bridge a gap: Their tales of dogs and adventure and violence carry boys from early childhood’s more innocent stories smoothly into the world of books written by and for men. They prepared them for the questions of life and death that these important stories would explore; they carried boys from woods and war games to actual war, to the kinds of books that were called great. I understood from a young age that the novels handed to me—about parties and friendships and babysitting—were pointing me somewhere else, somewhere deemed lesser. As C. S. Lewis puts it in his final Narnia book, The Last Battle, a girl is excluded from that world’s heaven because of her growing interest in “nylons and lipstick and invitations.” I felt the danger of being shuttled down that same path, a trajectory from princesses to love stories and then to nowhere. And so I turned up my nose at any book that wanted me to care about girlish things. I loved Real Books, and I wanted to be a Real Writer, and so I devoted myself, eagerly, to boy books.

Paulsen is known for his distinct writing style, which I’d characterize as more experimental than the floral, lush writing of your average book for eight- to-twelve-year-olds. In Hatchet (Macmillan, 1986), probably his most famous book, a boy survives a plane crash in the remote Canadian woods, but has to learn how to live with no equipment except for the titular tool. His experiences of hunger, fear, despair, and anger are rendered in short, jagged sentence fragments, with one word alone in a sentence or paragraph, stuttering along as the boy’s mental state swerves from one desperate extreme to the next:

And there came hunger.

Brian rubbed his stomach. The hunger had been there but something else—fear, pain—had held it down. Now, with the thought of the burger, the emptiness roared at him. He could not believe the hunger, had never felt it this way.

Those short sentences of Biblical power and importance; that escalating comma splice, that dropped subject; that placing of feeling and sensation (hunger, emptiness) as subjects of the sentences; all of these wonderful, strange things, I had never seen fiction do before. In many ways, Paulsen is a kid’s Hemingway. Notice the repetition, the building momentum and simplicity of phrasing in these paragraphs, all trademarks of Hemingway:

Divorce.

The Secret.

Brian felt his eyes beginning to burn and knew there would be tears. He had cried for a time, but that was gone now. He didn’t cry now. Instead his eyes burned and tears came, the seeping tears that burned, but he didn’t cry.

For a young reader who had yet to discover Hemingway, it felt like a revelation: Could you even do that? I wondered. Have a word alone on its line, a phrase speaking for itself? Was it allowed? I was thrilled.

Maybe this was what readers felt when In Our Time (Boni & Liveright, 1925) thundered onto the literary scene. These techniques seem old hat now, but I know that Paulsen was my first encounter with style. Other middle-grade books told their stories in the deliberately old-timey language of fantasy lore, or else they wrote in an unremarkable, accessible speech designed to get out of the way while the talking animals and magical spells and babysitter dramas held your attention. But what held my attention in Paulsen’s stories was his style, almost more than the story. I’d never hunted in the woods, never endured thirty-below temperatures or sliced open a dead animal (or wanted to). But I knew I wanted to write like this writer.

In his books, Paulsen does not patronize his young readers, or coddle their emotions, or doubt their ability to handle tough questions of life, death, and mental stability. He shows injury, blood, and violence. Above all, he does not sentimentalize nature or the animals struggling for survival alongside his human protagonists. He is interested, above all, in clarity and truth. All the romance and cuteness projected onto animals in other literature has no place in a Gary Paulsen book: In his memoir Woodsong, after describing the torturously slow death of a deer at the teeth of a pack of wolves, for example, he recalls the wolf pausing to look at him, and then resuming the kill, and writes, “Wolves do not know they are wolves. That’s a name we have put on them, something we have done.”

I don’t have to look back at my copy of Woodsong to remember that line; it’s there, sparkling in my memory, as an example of some of the simple, visceral truths Paulsen delivered to twelve-year-old me, stunned by the open brutality and searing honesty of his writing. This was a kind of beauty that I had not experienced before. I was thrilled by it. After reading a Paulsen novel, I’d rush to the computer and hammer out my own fictional story of survival, full of sentence fragments and words alone on the page. I was a Writer. I was creating my Style.

![]()

Writers can’t always choose what their first encounter with style will be, and how it will shape them and their writing, but the mark they leave is indelible. No one told me, at my all-girls’ school, that Hemingway and Steinbeck were greater writers than Austen or Woolf, but I picked up the message all the same: When I took American Literature we read nine male authors for every female one. I leaned eagerly toward these tough, masculine writers, feeling something hard and diamond-bright and utterly uncompromised in their stoic sentences. I was really a raging little sexist when it came to my tastes. And because I was told I could not love Paulsen’s books, because they were not for me, I loved them harder, determined to embrace his aesthetic in my own writing, so that I’d be worthy and not trivial.

I must have showed my disdain, because in the last week of high school, a favorite teacher tucked a picture of Eudora Welty in my mailbox like a forbidden missive, along with her quotation, “A sheltered life can be a daring life; for all serious daring starts from within.” I picked up a collection of her stories in my first year of college and began to learn that this kind of clarity and truth was not exclusively the domain of men. I discovered Flannery O’Connor and Toni Morrison, and learned that women’s lives contained their share of brutality and shocking violence. I was thrilled by Muriel Spark’s clear-eyed cruelty, the vicious hairpin turns of a great Alice Munro story, and the hair-raising fear and dread of Samantha Hunt’s work. I read Marilynne Robinson and saw how Biblical power and poetry could go hand in hand in a girl’s story too. That in fact the stories of women were stories of survival in their own way, and that women, too, had life-and-death decisions to make, when the stakes of their lives were laid bare.

In my writing, I’m still drawn to a Biblical punch of language, a one-liner stamped into the page, a comma splice when the going gets tough for my characters. Paulsen led me through secret, tree-lined pathways to the spirituality and truth I wanted in my work. My second novel is my attempt at a survival story, with frozen nights and snow and blood, but my hero is a girl in the woods, struggling to survive being a girl in a place that won’t have her. It is about a survivalist cult living in the wilds of Northern Michigan. The opening scene, of a young girl skinning a porcupine she’s killed, is pure Paulsen, even as it’s my own invention. The novel follows the girl’s struggle to free herself from the cult’s clutches—and from the influence of the cult’s charismatic leader, her father. She has been shaped into a weapon of his militaristic religion, but she loves the beauty of her wild upbringing. I wanted to capture how the wilderness, the certainty of nature, keeps her tethered long past reason. The imagery of Woodsong and Winterdance entered my dreams, formed my lexicon for beauty and harshness and the silvery truth of life and death that exists in the best nature writing. I know I’ll always be haunted by it. The novel is my love letter, and my rebuke. For all the books I read by Paulsen—and he wrote two hundred of them—I can’t think of one with a girl in it.

When I learned of Paulsen’s death in October 2021, I felt a jolt of sadness, as one does with the loss of a friend. Paulsen will always be one of the few writers who can make me feel so strongly—feel the potent memory of reading his work as a kid, the thrill of discovering aspects of storytelling I had never seen before; experience the genuine emotion he allows his characters to show. Returning to Paulsen’s books, I can still see the inventive way he reached out to young readers and had the courage to show boys’ feelings: Unlike in other “boy books,” Paulsen’s protagonists keen with grief and struggle not to cry. They are moved by the beauty of nature and they long for things they can’t have. Maybe that’s why I could find my way into their minds and hearts as a reader; Paulsen showed the simple truth that boys have feelings too, and that feeling is at the center of every great story.

As writers, we take the stories that made us dream as children and spend a lifetime re-imagining them, arguing with them, re-visiting them for solace. Sometimes we write to return to the places that comforted us as children, but we return to these places changed. When I was a kid, at night while lying in bed, I often listened to the cassette tapes of Hatchet and its sequel The River, in which the boy returns to the woods and must raft down a river to save his companion. I could close my eyes and imagine myself into the characters’ heads, even if they were boys, even if the story had not been written for me. I would fall asleep to the sound of its story of howling wolves under a Minnesota moon. Today, Paulsen’s books remind me of the girl I was: lonely and in search of a friend in the stories I read, looking for myself in those stories as well. I wanted so badly to become not the boy in the woods with the hatchet, but the writer hunched over a typewriter in a salt-stained parka in a cabin somewhere, writing words that other people thought mattered. I’ll always be reaching for that elusive authority in the stories I write. And I’ll always be that girl, let loose by Paulsen’s storytelling: I still know how it felt to turn the volume low and press play and close my eyes; the words slid into my mind and shaped me, I’m sure of it, and the tape ran on until it reached the end of that side, but by then I was fast asleep, dreaming of the stories I’d tell.

Blair Hurley is the author of The Devoted (Norton, 2018), which was longlisted for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize. Her second novel, Minor Prophets, was released by Ig Publishing in April. Her work is published in New England Review, Electric Literature, the Georgia Review, and elsewhere. She is a Pushcart Prize winner and an ASME Award for Fiction finalist.