Set on the lush, gorgeous Malabar Coast in the Southern Indian state of Kerala, Abraham Verghese’s latest novel, The Covenant of Water (Grove Press, May 2023), follows three generations of a family—spanning a time period from 1900 to 1977—who are beset by a strange curse: A member from each generation has drowned unexpectedly. Drawn from the author’s own family lore, The Covenant of Water is a story that examines the intricacies inherent in love, faith, family, and medicine. The novel’s beating heart is a character known only as Big Ammachi, which translates literally to Big Mother, the matriarch of this large, extended family. Sent off on a boat to be married at the tender age of twelve, to a man almost thirty years her senior, Big Ammachi is witness to an extraordinary shift within her small Christian community as well as in India when, during her long lifetime, it finally shakes off its 200-year-old colonial yoke and comes to life as a nation. The Covenant of Water is also a love story, the kind that one doesn’t often encounter in contemporary fiction—a monumental story of love not just between two individuals, but also between people and the land, between land and the water, and between art and science.

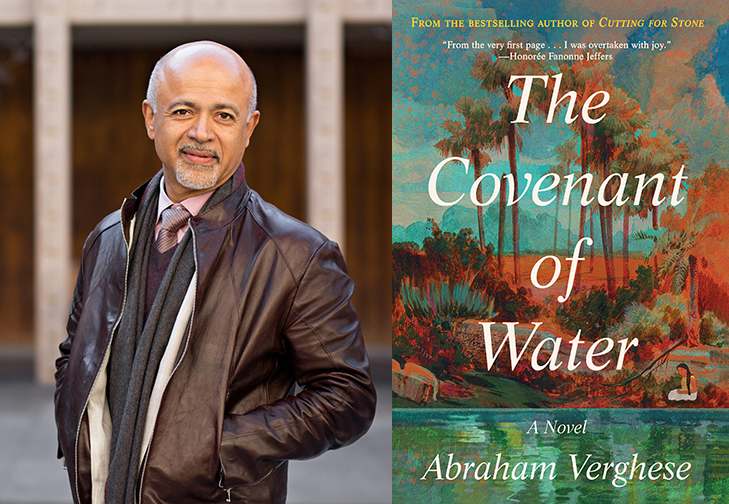

Abraham Verghese, author of the novel The Convenant of Water.

“Fiction is the great lie that tells the truth,” writes Verghese in The Covenant of Water. As a young doctor specializing in infectious diseases at Johnson City Hospital in Tennessee, he was deeply moved by the overlooked tragedy of the AIDS crisis he saw unfolding there. So he abruptly quit his tenure-track position, cashed in his retirement, and moved with his young family to Iowa to pursue an MFA at the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His goal: to look for language that could express the devastation of an unprecedented medical and spiritual crisis in the American heartland. The resulting book, My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story of a Town and Its People in the Age of AIDS (Simon & Schuster, 1994), was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in nonfiction.

Abraham Verghese is also the author of the memoir The Tennis Partner (Harper, 1998) and the novel Cutting for Stone (Knopf, 2009), which remained on the New York Times bestseller list for two years and sold 1.5 million copies in the United States alone. Across all four of his books, his project is to trace the connections among the continents of love, duty, loyalty, and heartbreak. He lives and practices medicine in Stanford, where he is the Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine. We met on Zoom in early spring to talk about the epic novel as a vessel for storytelling, the place from which writing flows, and geography as character.

I love the title of your book, The Covenant of Water. How did you decide on water as the through line, as the central motif of your novel? What does this title mean to you?

I think titles, by their very nature, should be a bit mysterious. Every reader takes away what they think the title means. For me, the final interpretation of a book is never my interpretation. It’s a collaborative act between reader and writer that should create a movie playing out in the reader’s head. If you write a novel set in Kerala, water is inescapable; it is the prevailing metaphor for everything. We’re talking about a land with forty-four rivers, countless lagoons, lakes, streams, back waters, fingerlike projections into the sea. Water is the great beating heart of the state. It affects the commerce, the industry, their metaphors, their way of being. You’re much more struck by that as a visitor than if you’re from there, where you might take it for granted. That’s where the water part of the title comes from. And “Covenant” because the novel wrestles with issues of faith and loyalty: the covenants that people make with each other in the form of marriages, or the covenant of being a parent, or the covenant of being in a certain profession, the covenant of being a priest or a doctor. You try the title out on a few people. If they don’t know what the book is about, or especially if they do, if it resonates for them, that’s a good sign.

The Covenant of Water straddles myth and reality. There are elements of magical realism, but you turn the volume way, way down on them. I was wondering about how you made those decisions, to balance between the worlds of myth or legend, and a plausible medical history for generations of this fictional family?

It’s interesting that you should ask about magical realism. Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera is one of my favorite books. I think that what one culture calls magical realism is the reality of another culture. In India we operate in the world of myth or magical thinking: Don’t step out at this time, don’t do this act at this time, perform this ritual before you enter or exit the house, etc. We’re surrounded by that. People also accept at face value that certain people have inexplicable gifts. We are not as sort of black and white in our questioning of these things, as we are, say, in the West. So, I didn’t think about the story in terms of fantasy or reality, I was capturing what is normal, everyday thinking in India, where people operate in this duality.

That’s so interesting, considering your background as a physician. How do you reconcile those two sides of your nature, the side that is embedded in science and physicality versus the side that is able to make room for magical thinking?

I always tend to resist that description of me as a physician and a writer. I clearly am a writer as well, but the physician feels central to my personality, my being. When I write, it doesn’t feel separate from medicine. The writing emanates from a deep interest in humanity, from a place of witnessing people at the most eventful moments of their lives, and often being a part of that moment. Admittedly, it’s maybe different from what other physicians might be doing. Physicians do have lives outside of the hospital and they choose to exert themselves in various ways. I came of age trained in infectious disease, just as HIV appeared. I think that really shaped me, watching these young men my age, dying of a fatal illness. It was so unlike any infection we knew of before, with fatalities in such large numbers. I feel like the writing came organically out of what I saw. My big worry, if I were ever to give up medicine, is that I wonder if I’d have anything to say.

I’d imagine that being a physician would also train you to look at life with a certain level of unemotional or clinical detachment.

I don’t think physicians are in any way spared getting caught up in the moral or emotional issues. In fact, we’ve done a disservice to physicians in the early parts of the last century, where the emphasis was on being objective, and keeping a distance. Your most powerful interaction with patients is revealing your own humanity and showing that you are moved by what they’re experiencing. If you’re dispassionate, you fail to make a connection with them. William Osler, a famous physician, said: It’s much more important to know what patient has the disease, rather than what disease the patient has. In other words, who the patient is matters. That person is a collection of histories, and of needs. As physicians, we’re taught how to take a history, the story of the illness; we also learn how to read the body for clues to illness. Sometimes I’m almost paralyzed in places like airports because I’m observing people’s gait as they walk with their bags, and I notice all kinds of pathology. It feels like a curse, and it also feels like a great privilege.

It was a great question. It’s not, by any means, that physicians are spared emotionality. It’s more that when needed we’re trained to be objective. But ultimately, I think we serve people best by being human, being empathetic to what they’re struggling with.

You mentioned elsewhere that you wrote a huge chunk of this novel during COVID, during the lockdown. I imagine that must have been an extremely stressful and busy time for you, as a doctor. I am wondering how you avoided burnout in both your practice and in your in your writing.

I’m fortunate to be at a large academic center. The brunt of the weight of this experience fell on our emergency medicine personnel, and on our wonderful interns and residents. As a senior member of the department with an administrative role, my efforts were occupied with trying to logistically manage limited amounts of resources and navigate public misinformation. I was affected by the epidemic in more personal ways. There were people I knew well who’d succumbed and physicians I knew who were dangerously ill. I think it found its way into the novel in terms of the emotions I was feeling. At one point, a close friend of mine was hovering on death’s door because of COVID. And meanwhile I’m writing about people suffering from an often fatal illness, and in a subconscious way the weight of what I felt for my friend lent itself to my understanding of what my characters were experiencing in a different time period. It also struck me that things aren’t that different today on the level of a person suffering with an illness, or someone looking at their life extinguish, or at the loss of their child. People find meaning in the same things: their faith, family, their memories. I feel that, as I get older, as a physician—this is not a condemnation of younger physicians—I don’t think I had quite the degree of empathy that my older physician self has. It has to do with one’s own approaching mortality. There’s a point when my characters become so real, they dictate choices. I may decide, this character is going to do this. But when you arrive at that place in the story, the character lays it out that that’s no longer possible. The choices that they’d make under pressure are very clear to them. I had to discover this.

I want to circle back on influences. You had mentioned Gabriel García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera, but interestingly you didn’t mention One Hundred Years of Solitude, which I think is probably Márquez’s most famous work.

I’d read One Hundred Years of Solitude before I came to writing, which was fairly late in life. At the time, I didn’t quite get the book. Meanwhile, I’d read Love in the Time of Cholera maybe ten or fifteen times. For whatever reason, maybe because of the character of Dr. Juvenal Urbino as a physician, there’s something about Love in the Time of Cholera that I admired more. It’s a huge love story. García Márquez has been a major influence, but there are so many disparate influences. It’s hard to pick one. I really admire John Irving as a grand storyteller. When I first read The World According to Garp—again, well before I thought about becoming a writer—I had this revelation that a novel could really be this grand in its ambition and scale. Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage is another huge influence.

While reading The Covenant of Water, especially the character who is a young Scottish physician, I’d felt an immediate call back to Of Human Bondage. It is one of my favorite books. I’m happy to know that you were influenced by Maugham.

Well, I was influenced by Maugham, but perhaps not in the way you’re thinking. For a generation of us physicians of a certain age, we were often called to medicine because of a book, and I came to medicine because Of Human Bondage. Something about the main character, Phillip, finding meaning in medicine, whereas as an artist, he didn’t have the talent, he didn’t have the genius. What I took away was that to be a great physician, you don’t need genius, you just need a curiosity about the human condition, you need empathy for your fellow human beings. Philip had that. It was less about Maugham’s writing style, which is fairly plain. It was his influence that brought me to medicine. The irony is that I came to medicine because of books. And now paradoxically, I find myself writing books. I’m a great admirer of the huge epic novel. You live through three, four generations, and you put the book down, it’s just Tuesday. I don’t think there’s anything in the world that can stop time the way a novel can stop time. The Brothers Karamazov, I think, is another example of just a huge sweep of a novel. And The Grapes of Wrath. When I read, late in life, The Adventures of Augie March, I thought, “Wow, if I only read this when I was much younger.” It's something a young person might read and realize that life has so many ups and downs; no one event should dissuade you, there’s more to come and more to come and more to come. I think the modern taste is more to shorter stories. I enjoy those, too; I love to read them. But if I’m going to take the time to write, I’m drawn to telling a bigger story. I’m less ambitious about portraying a slice of life than I am about portraying life itself.

Naheed Phiroze Patel is a graduate of the MFA program at Columbia University’s School of the Arts. Her writing has appeared in the New England Review, the Guardian, Poets & Writers Magazine, Chicago Review of Books, HuffPost, Scroll, Bomb, the Rumpus, and Asymptote Journal, as well as on Literary Hub, Public Books, the PEN America website, and elsewhere. Her debut novel, Mirror Made of Rain, was published by Unnamed Press in May 2022.