In September of 1994, I was a first-year student at New York University’s graduate creative writing program. That’s another way of saying that in September of 1994, I was in a constant state of terror that I was about to be outed as an imposter by all the talented writers around me, mixed with horror at my hubris for thinking I could write anything readable, let alone good, combined with the surety that I must be the only one in my program who felt this way.

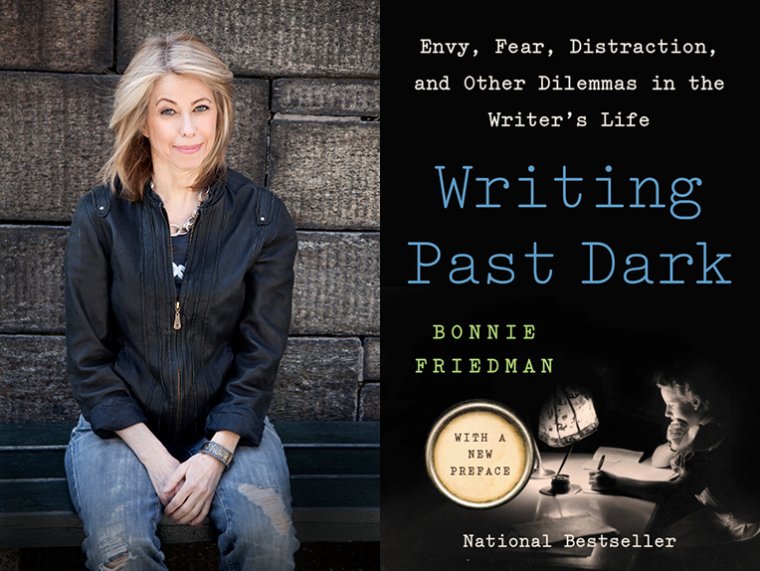

Bonnie Friedman, whose classic guide for writers, Writing Past Dark, was recently reissued by Harper Perennial.

Walking the streets of Greenwich Village one fall afternoon, most likely trying to drown out the sound of the internal voices squawking in my ear, I wandered into Three Lives bookshop on the corner of Waverly and West 10th Street. At the display shelf to the left of the register, a slim grey volume caught my eye. Writing Past Dark, the bold black title letters announced. Then the subtitle in a disarming, intimate cursive, set off in a yellow box like a beacon from a lighthouse cutting through the fog: Envy, Fear, Distractions, and Other Dilemmas in the Writer’s Life.

How did it know? How did this little book see right inside my head and know?

I bought it immediately and that night read it cover to cover. Bonnie Friedman’s disarming, revealing, whip-smart essays were indeed a beacon from a lighthouse. Friedman had felt all the terrible, secret feelings I was feeling when she started on her path as a writer too. And even more exciting to a new writer: She corralled those feelings into this book—this book I turned back to again and again in my graduate school years to remind me that envy and fear and distractions were part of the deal, not proof that the deal was off. This book became my dog-eared friend, my confidante through margin scribbles, and a sign of hope I needed to help me write past—and despite—my own darkness.

Now Harper Perennial has reissued Writing Past Dark, with a new preface by the author, for a new generation of writers, so they might find in it the friend they need, just when they need it. The following interview is culled from a series of conversations Friedman and I had as she reflects back on Writing Past Dark, and her thoughts now about the dilemmas—and joys—of the writer’s life that she’s learned since the book first dropped.

What did you feel was missing in your early years as a writer that propelled you to turn to the subjects you addressed in Writing Past Dark?

I had no idea how to navigate the emotional side of the writer’s life. All my education in writing concerned the technical aspects of craft. But that wasn’t what was tripping me up. I lacked self-confidence, and had no access to any really respectful, in-depth examination of how to manage one’s feelings as a writer. Being told “You have to believe in yourself” or “When you’re knocked off your horse, get back on!” doesn’t generally help much. If anything, these kinds of statements usually compound the shame you have if for some reason—some perhaps significant and suggestive reason—you can’t do that. I found the way people addressed the emotional issues that come up in the writer’s life to be blithe and not very useful, even though these issues have everything to do with whether or not you succeed and how long it takes you to succeed.

I also wanted to make sense of semiconscious behaviors I indulged in that I could only half-acknowledge to myself. One example: opening the New Yorker as soon as it arrived each week and inducing a debilitating state of envy, even if I had been in the middle of a good writing day. It was perverse. But I did it. And I wanted to understand why. I suspected that my hidden behaviors were similar to others’ hidden behaviors. I was curious about them. I had a suspicion that they would repay investigation, that they had secrets to give.

What were the fears that bubbled up for you when writing about fear?

I’d never had writer’s block until I got the contract for Writing Past Dark and I’d been writing committedly for a decade. But now I was afraid. I had this feeling that I’d been given permission to go to lush, dark places holding up a lantern. And I didn’t want to squander the opportunity. That was really my fear. And it was part of why I couldn’t write the book immediately. I think that the desire to write one’s very best book, the book you know you have it in you to write, is very often the cause of why people can’t write.

So instead I wrote a long essay about The Wizard of Oz. It was all about the hypnotic message embedded in the film that girls should abandon the big world in favor of home—a trade-off boys don’t have to make; if anything, boys receive the opposite message: that they must leave home to save it. I was afraid of writing my book in a way that was glib. I was afraid of finding myself back in the ordinary, complacently comprehensible black-and-white world before I’d made my journey.

I remember a dream I had at that time in which I found a cigar box containing the wood shafts of two dip-ink pens and some scallop-edged postcards that Cynthia Ozick had, in my dream, lost on her honeymoon. Obviously Freudian. It was a dream about lost potency and misappropriated magic. And, I suppose, as with my fascination with The Wizard of Oz, it was also about the fear of abandoning my mother by becoming someone else. For those of us who’ve been caretakers, as I was of my fragile mother, there is a terror of withdrawing attention from the outside world to attend to ourselves. And there is also, as Melanie Klein would have pointed out, guilt at surpassing, guilt at wanting to steal back the gifts that have been projected outward by the excessive admiration a girl often feels for her mother or her best friend.

Receiving the endorsement I’d craved my whole life destabilized me. I’d thought that it would kind of immediately infuse me with the confidence I’d craved, but endorsement doesn’t work like that, at least it didn’t for me. And so I had to figure out how to write a book that I didn’t feel the equal of, that I was afraid wouldn’t be as worthwhile as it should be. In the end I had to let myself write my book in my own quirky, associative, exploratory way. Gradually one realizes that the only way to write one’s book is to continually give up the dream one had for the project.

What did you learn about yourself in relation to some of the biggest “taboos” you tackled, such as envy, that you didn’t know before writing Writing Past Dark?

I learned that I was drawn to people I envied. I learned that I had believed that I’d acquire their intelligence and originality and sensibility by being close to them. I learned that this was impossible. I learned that these brilliant friends weren’t waiting for me to become someone more extraordinary so that I would finally deserve their friendship. They valued our friendship as it was. A few of them were insecure and wanted admiration. Many probably didn’t see me as inferior; they saw something in me I didn’t see in myself. Nevertheless, because I didn’t know what value they saw in me—I felt blandly meager in their company—I had to estrange myself from my glorious, intellectually intimidating friends in order to write my book, and this was confusing and painful, for me and for them. I knew I was behaving poorly but I couldn’t stop if I was going to write my book. In all of this I assume that I’m not unusual.

When the book was published, I learned how very common many self-defeating issues are because the book hit a nerve. Other people felt guilty about writing about their families, other people were frightened of embarrassing themselves by putting their idiosyncratic mess on the page. The ways I was weird turned out to be the ways that others are weird; the things I was ashamed of were what other people are ashamed of too. Although actually, I never felt ashamed of being envious, since it was such a painful state to be in. It’s like feeling guilty about being punched.

And I learned that exploring taboo subjects can unleash a great power, the power that the taboo had been holding in lockdown.

When Writing Past Dark was published, what responses to the book surprised you the most?

I was surprised and have continued to be surprised by the number of people who told me the book was important to them. By the people who said they attribute their own novel or memoir to having read Writing Past Dark.

I was surprised, too, by the occasional violent rage that my book inspired. I recall a handwritten letter—a piece of hate mail—saying that I ought to be barefoot and pregnant and never allowed to write again. This was long before the idea of trolling someone, or just misogynistic attacks on any woman who achieves anything. I had no context for it. It was just peculiar.

I also remember a man at the Barnes & Noble in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, a man who was obviously attending my event because he was accompanying his wife, and who looked so enraged by my talking about envy that it appeared to me as if a skillet had struck his face and just clanged it frozen with fury. And I remember another man who sat on the floor with his back to me while listening to my presentation, facing the bookshelves as if trying to choose a book, just occasionally scratching or shifting for half an hour, listening closely without wanting to acknowledge that he might be able to benefit. This, too, told me about the verboten nature of what I was examining—the fury it aroused in some, and the covertness in others.

What would the final chapter be if you were writing it now?

I’d write about listening to those who galvanize and nurture your writing. And that just because someone’s smart and sensitive doesn’t mean they will be helpful to you in the feedback they give. They might even actually be correct, but it stops you. It doesn’t further you. It sets you off course. They’re just not on the same wavelength. Or they just come from a slightly different worldview and want things explained that shouldn’t be explained. People can be very intelligent and actually even correct in their response to your work but nevertheless misleading and wasteful of your time. So you mustn’t listen to them.

You have to grow your own confidence, and for many of us this comes from teaching, from discovering that we know a great deal about the subject we’ve been studying and loving. For years I taught workshops out of my living room. That was some of the most fun teaching I ever did. It’s good to see how you can grow your authority and confidence because that does translate to the page and help you take risks and claim space.

Also, finally, I’d acknowledge how so many of the things that limit us are systemic but it’s hard for us as separate individuals to notice this. If I were writing a last chapter to my book, I’d include that, too.

Anne Burt is editor of the essay collection My Father Married Your Mother (Norton, 2006) and coeditor, with Christina Baker Kline, of About Face (Seal Press, 2008). Her short story, What Birds Want, won Meridian’s 2002 Editors’ Prize in Fiction. She is at work on a novel.