Before he found his voice in memoirs, Frey wrote screenplays for a living, starting in 1993. By that time, he was finally free of alcohol and drugs and was faced with the decision of what to do. “I didn’t have the resumé to do anything,” says Frey. “I had a long criminal history, I had a long drug and alcohol history, I wasn’t going to get a job at a bank or get into law school. I just wanted to find something I could do that would make me happy, that would make me feel good about myself.” Frey finally found it: writing. But the author, brushing off any romantic notions about his life, says it was a simple, practical decision—the clouds didn’t part, there was no epiphany. “If I’m going to do it, I want to buy a computer,” he remembers thinking, “because I don’t want to write on paper.”

That pretty much sums up Frey’s outlook as a writer. Instead of inspiration, it’s about confidence and hard work. He goes about his writing life the way he went about his recovery: very deliberately, very methodically. “I wanted to be a book writer, but at the time I didn’t think anything I was writing was any good,” he says. “And I was tired of making my money either illegally or in a fashion that was just mindless drudgery. I thought that, if I could write a screenplay and sell it, that’s a better way to live than, you know, working at a bar.”

The first two screenplays Frey wrote were, by his own admission, “just awful.” The third one, which he thought was “readable,” was sold. A couple of rewrites later, the film was released. The 1998 romantic comedy Kissing a Fool, a vehicle for Friends star David Schwimmer, was a flop and was met with almost universal critical scorn.

“I didn’t sit down with the sort of attitude that I think a lot of first-time screenwriters sit down with, that I would write a masterpiece,” he says. “I sat down and wrote something that someone would pay me money for, something as commercial and as sellable as I could. Because that was what my goal was—cash. The goal wasn’t an Academy Award or indie credibility—it was cash for services rendered.”

After five years in the film industry, however, Frey set out in earnest to find the voice in which to tell the story of his recovery. And for this he needed something more than a commercial screenplay. One thing that occurred to Frey was that most of the writers he loves—Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Céline, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Kerouac, and Bukowski—taught themselves how to write. “They didn’t go to school for it, they didn’t have mentors who explained to them how to do things or not,” he says. “They just sat down and started working. They kept working until they were able to do what they wanted to do.”

And that’s what Frey did. “I figured if they could do it, I could do it. I figured I’d give it shot,” he says. “All I have to be able to do is sit down and write one sentence. And if that sentence is good, I can go on to the next sentences. And if you add the sentences up over a certain period of time, hopefully, that’s something that’s worth reading.”

But Frey didn’t want to be just a writer—he wanted to be unique. “I read all these people and I started thinking about what they all had in common,” he says. “And the most obvious thing was that, when their books came out, there was nothing like them that had preceded them. We read Hemingway now and people are just like ‘Ah, that’s Ernest Hemingway.’ To this day, if you pick up Hemingway and read a page of it, you know it’s him.”

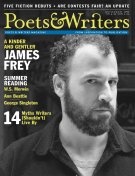

And so, Frey reasoned, he needed to find a style of writing that was new, fresh, unlike anything that had come before. It took years to find that voice, he says. “And then it was just a matter of getting it down.” The result was A Million Little Pieces. Whether Frey qualifies as a modern-day Hemingway is debatable, but many would agree that Frey’s writing style is indeed unique, including publisher Nan A. Talese. “It was a huge honor to be published by Talese,” he says. “When I wrote the first book, if I could have chosen whom to be published by, anyone in America, it would have been her. As cheesy as it sounds, it was a dream come true to get the call from her.” These qualifiers—his hesitance to come off as “cheesy” or “melodramatic” at the top of the conversation—point to a kinder, gentler James Frey. Or at least one more aware of how others perceive his confidence.

It wasn’t always this way. For a couple months in 2003, Frey was portrayed as The Author Who Is Talking Shit. The trouble started in a New York Observer profile—his first—which appeared before the publication of A Million Little Pieces. Here’s an excerpt of the famous quote: “I don’t give a fuck what Jonathan Safran whatever-his-name does or what David Foster Wallace does. I don’t give a fuck what any of those people do. I don’t hang out with them, I’m not friends with them, I’m not part of the literati.”

Two years later, not being part of the literati is still the case. “I don’t particularly care if I’m part of the publishing culture or not,” Frey says, taking a sip of his Diet Coke. “And that’s fine. I’m very comfortable that way.” Today, however, the author sounds somewhat conciliatory, even mentioning David Foster Wallace as one of the writers he read when finding his voice.

Today Frey avoids the salty language, but he sounds just as deliberate and confident. No F-bombs are dropped. Instead, he states what he sees as the facts of his success. “I don’t think of what I do as being anything special, or requiring any special mental capacities or intellectual capacities. I look at what I do as work,” he says.

“I think part of what holds people up is a fear of failure, or a fear of criticism. And neither of those things scares me at all. If I fail, I fail. I give it my best shot every day. And I think, if anything, that’s my gift. It’s the ability to work really hard, very, very consistently. Now, I know a lot of people who are smarter than me or are probably more talented than me or more naturally gifted than me. But what I can do that they cannot do is go back for eight to ten hours every day. And it seems to be working for me.”

Daniel Nester is the author of God Save My Queen and God Save My Queen II, both published by Soft Skull Press. He edits Unpleasant Event Schedule.