For nearly two weeks in 2018, poet Doug Van Gundy and photographer Matt Eich interviewed residents of Webster County, West Virginia. They talked with gravediggers and teachers and diner cooks. They had coffee with an ex-military man who sold sawmill equipment; they visited the county clerk’s office, filled with boxes of election materials; they watched an elementary school Christmas play and concert. All along the way they asked those they met: What is it like to live here? What do you wish others knew about your life? With permission Van Gundy would record each conversation or take notes, and Eich would make photographs.

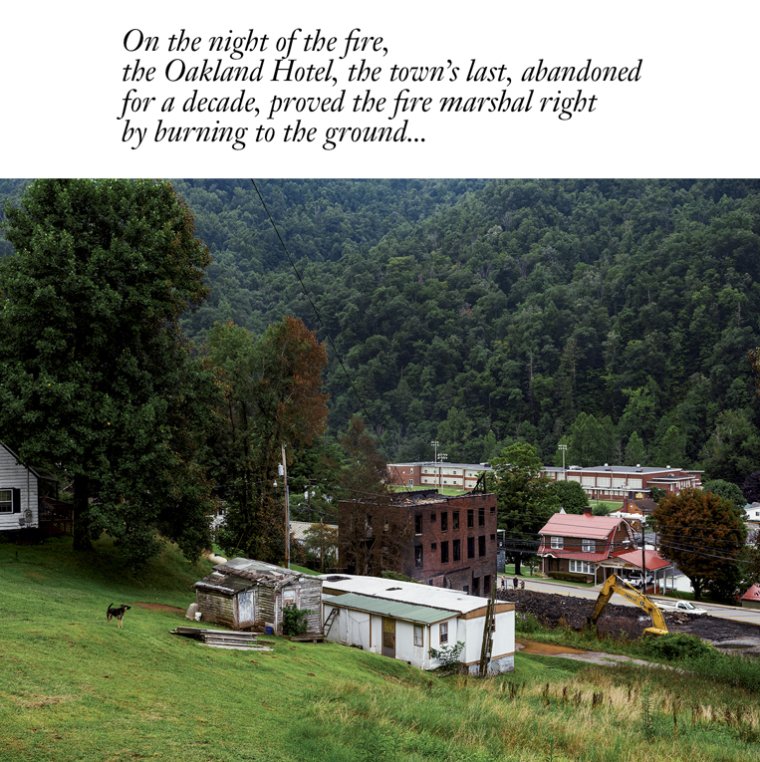

An excerpt of Doug Van Gundy and Matt Eich’s docupoetry project about Webster County, West Virginia. (Credit: Matt Eich)

The pair weren’t there to report on the area for a traditional newspaper article but rather to create a portfolio of poetry and photographs that documents life in the county, which is home to fewer than ten thousand people and is one of the state’s poorest areas. The piece, which was published in the Guardian in May 2019 with an introduction by writer Elizabeth Catte, is the first in a series of similar portfolios commissioned by Alissa Quart, the executive director of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project (EHRP). Founded by writer and activist Barbara Ehrenreich, EHRP is a journalism organization that commissions projects covering poverty and economic inequality in creative and unconventional ways. EHRP then copublishes the pieces in media outlets such as the New York Times, the Guardian, and Vice.

The poetry of the EHRP portfolios reflects contemporary poets’ burgeoning engagement with the genre of documentary poetics. Quart describes the genre as a kind of socially engaged poetry that often uses nonliterary texts—news reports, legal documents, and transcribed oral histories, for example—and sometimes incorporates original reporting. Also called docupoetry, the genre historically tends to focus on relating the experiences of people whose stories might have been misrepresented or overlooked; documentary poets often cite Charles Reznikoff’s 1934 book Testimony and Muriel Rukeyser’s 1938 long poem “The Book of the Dead” as early, defining examples of the genre. This summer Quart began developing two new portfolios of documentary poetry and photographs that seek to do this kind of reported, civic-minded work: She commissioned poet and political scientist Celina Su and photographer Annie Ling to portray the experience of floating immigrant communities in New York City, and is in talks with poet Erika Meitner to create a piece about gun ownership. Quart, who is herself a poet, has also written an essay on documentary poetry, published in the November issue of Poetry, and included a documentary poem about abortion clinics in her recent collection, Thoughts and Prayers (OR Books, 2019).

With the EHRP portfolios Quart hopes to bring fresh perspective and humane language to people’s hardships. “We have this potential for empathy fatigue—so how do you cut across that when you’re trying to represent pain or other kinds of struggle?” she says. “One of the ways I think we can do so is formal. I think hybrid forms like docupoetics do informational and emotive work that a lot of traditional journalism might be unable to do.” She argues that many formal poetic devices, such as white space, different registers, lineation, and refrain, can help “liberate us from some of the poverty narratives just a little bit—let some light into them.”

Van Gundy and Eich aimed to do this with their work in West Virginia, which is also Van Gundy’s home state and which he says is used as “a shorthand for poverty, for rural, for conservative, for ignorant, for fill-in-the-blank.” He and Eich tried to let a range of voices and stories of West Virginians come through; Van Gundy’s poems set the words of those he interviewed alongside specifics like the names of old coal camps and the image of a white-haired woman crossing the street. “The combination of photography that documents the landscape and the physical trappings of a person’s life with poetry that documents the interior and emotional trappings of someone’s life in the small, specific details is about a kind of seeing,” Van Gundy says. “It’s about trying to bring an honest eye to the seeing of people and letting them be who they are.”

Although many documentary poets hope to bring this honest vision to their subjects, the work raises ethical questions about who is being depicted, and by whom and how. Quart so far has only asked people to document issues or communities they have experience with, noting that to do otherwise could result in touristic work. Van Gundy, who teaches at West Virginia Wesleyan College, believes many people were willing to talk with him and Eich, a resident of Charlottesville, only because they were local. “I know that West Virginia is not always represented accurately or favorably in movies and books and newspaper articles and whatnot,” Van Gundy says. “So I said to people, ‘That’s not what we’re going to do here. We’re going to let you talk, and then we’re going to tell your story.’” The pair also took pains to not portray West Virginia in a single light—simplification of one’s subject being another possible peril of any documentary work. Quart says their portfolio is in no way “miserablist,” and Van Gundy says he strove to avoid being nostalgic or playing into a certain stoicism he believes West Virginians sometimes uphold. “I think that romanticization—taking struggle, poverty, and lack and clothing it in nobility—does people a great disservice and keeps them from the dignity and the resources they deserve,” he says.

Going forward Quart plans to continue publishing poetry portfolios; she is open to pitches, and EHRP will pay for the project and some of the reporting costs. Quart is excited to bring her journalistic expertise to poetry; when she began writing poems, she found the poetry world very “heady” and sect-like, with “language poetry on one side and MFA poetry on the other.” She turned to journalism because she wanted to be focused externally and reach a larger audience. Now with her work at EHRP, she can merge the two interests. “This is my lifelong journey…to bring politically minded and broadly intended impulses back to poetry,” she says. “It’s a personal desire of mine to read that and enable others to make that kind of poetry.”

Dana Isokawa is the senior editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.