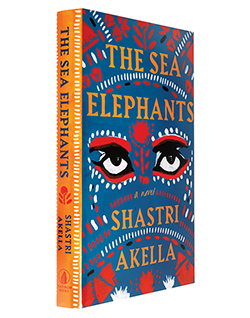

Shastri Akella, whose debut novel, The Sea Elephants, will be published by Flatiron Books in July, introduced by Naheed Phiroze Patel, author of the novel Mirror Made of Rain, published by Unnamed Press in 2022. (Credit: Akella: Subhadra Madhavan)

![]()

Shastri Akella’s poised, elegant debut, The Sea Elephants, is a bildungsroman of a young man who joins a street theater group in India after fleeing his father’s violent disapproval, the death of his twin sisters, and his mother’s unfathomable grief. It is a story about queer desire, the comfortable lies families tell themselves to survive, and art’s power to say the unsayable, to help us win back ourselves from the shame and self-disgust that society often deploys to control us.

In India queer existence is still relegated to the margins; it is precarious, ephemeral, endangered. It was only in 2018 that the Indian Supreme Court struck down a British colonial-era law that criminalized homosexuality. As of this writing, Indian law does not recognize same-sex marriage or civil unions. While there is a rich, storied tradition of queerness in South Asian art, culture, and mythology, queer literature is still a relatively sparse canon. This makes Akella’s novel, and his voice, all the more important—an infusion to a collective oeuvre that deserves much more far-reaching attention than it has received so far, both on the Indian subcontinent and abroad.

I was struck by an exchange between the narrator, Shagun, and his father at the start of the novel, in which his father asks Shagun about his favorite god. Can you talk a bit about the role Hindu mythology plays in the novel as well as in the framing of traditional ideas of masculinity?

Hindu mythology, in both oral and written forms, abounds with queer and trans characters. However, a fleet of political invasions on the subcontinent triggered the age-old fear of “the great replacement.” These original texts were supplanted with rigidly structured heteronormative versions: stories where straight upper-caste couples are at the top of the hierarchy, followed by the ruling and the agrarian, landowning caste. A celebration of the “masculine” cis man led to a reframing of Hanuman only as a fierce, masculine god—the version that Shagun’s father wants him to imbibe. The Sea Elephants presents myths in original and censored versions but without being didactic.

In your novel Shagun joins a traveling theater group in his search for meaning. Is there an overlap between the queerness narrative and the street theater narrative? What kind of research went into writing that?

I worked with a street theater troupe in India for three months, traveling with them, writing the stories they performed. I often relocated myths to the present day to accommodate current issues or retold them from the perspective of a minor character. The myth of the sea elephant was one of the first stories my grandmother told me. Once upon a time, the gods and the demons churned the ocean to mine its treasures. All kinds of wealth rose to the surface, including the first sea elephant. Pearl white, with six tusks. Beguiled by his beauty, the gods claimed him and took him to heaven. As a child of six I was shocked. How could they just take him away? What happened to his kids and friends? Years later, when the theater troupe said they wanted to perform that story, I found a way to answer those questions: by extending the story, by showing the gods apologizing to the sea elephants for stealing their ancestor and offering them reparations.

Shagun’s boyfriend is Jewish. I am sure many readers would be surprised to read about the rich history of Jewish communities in southern India. How did you learn about it?

When I discovered the history of Jewish migrations to India, I followed my hunch and got a research grant that funded my trip to Cochin, in the state of Kerala. The Jewish families I met were welcoming, sharing meals and stories with me. The persecution suffered by their ancestors, forcing them to flee to India circa 970 BCE, the community they formed nevertheless, resonated with the ways in which I was thinking of what it means for my narrator, Shagun, and individuals like him to have an authentic existence. A lot of what I learned made its way into the book, including Judeo-Malayalam, a language created by early Jewish settlers, a mixture of Hebrew and Malayalam. It made sense for Marc, the love interest, to come from this incredible community.

Could you talk a bit about your novel’s arc from its initial drafts to when it landed on your editor’s desk? What changed while editing for publication?

I thought I was asexual until I came to the University of Massachusetts in Amherst to do an MFA. In a fiction workshop my professor Sabina Murray said my novel seemed to want to be a gay love story. After a supportive conversation with her, I began therapy, came out, and my narrator came out with me. Eight years separated the version I submitted in Sabina’s class and the one that landed on the desk of my editor, Caroline Bleeke. Collaborative editing helped each draft approach its final version. Fellow writer Andrew David MacDonald’s feedback helped the novel find the apt starting point. My agent Chris Clemans’s suggestions helped me emphasize the story’s key priorities and give minor characters fully realized arcs. From Caroline’s potent feedback, the novel’s final structure emerged, the one that felt the most organic to telling the story I intended. This novel was raised by a village.

What would you say are your major literary influences?

Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, which I read every year for my birthday, taught me how to write characters who inherit bleak worlds and still find room for wonder. Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, which includes comic-book stories alongside the main narrative, taught me how to incorporate myths alongside my novel’s main story. Douglas Stuart’s fiction [Shuggie Bain and Young Mungo] taught me how to construct well-rounded queer characters who are products of the family and class they’re born into.

An excerpt from The Sea Elephants

ARRIVAL

My father left the country the year my sisters were born. He returned six months after I watched them drown in the Bay of Bengal.

My sisters’ funeral dinner was scheduled to coincide with the day of his arrival. Some relatives came over that morning to participate in the ritual. When I got back home from school, I found them sitting cross-legged in the foyer: fifteen women, the henna on each left palm drying to a russet circle of mangoes and leaves. The air tingled with excitement. And I understood. My father was here.

![]()

At dusk, we all filed into our backyard. I was still in my school uniform. We formed a circle around a priest. He read aloud a Ganesha hymn, and we chanted after him. We sat down cross-legged. In front of each of us was a banana leaf that held a heap of lemon rice surrounded by small pools of lentils, aloo-gobi, mango chutney, and yogurt. We started eating in the light of paper lanterns that ran from Ma’s window past the well to the outhouse, their amber bellies glimmering against the slowly darkening sky. The lighthouse on the banks of the Bay of Bengal swept its illuminated arm across the evening at nine-second intervals.

I avoided looking at my parents. The priest stood in our midst and watched us eat. He rubbed his potbelly and grinned at anyone who made eye contact with him. I didn’t want to be grinned at, I certainly didn’t want to grin back, so I looked away from him as well.

Suddenly, Ma called out my name. “Shagun? Where are you?”

The conversations around us were suspended.

“Shagun?” she called again.

The woman to my left hollered, “Your son’s here.”

Ma dropped her head a little, leveled her eyes with mine, and asked, “Why won’t you respond when I call you, son?”

I cupped a palm around my ear and leaned toward her.

“This is your father,” Ma announced.

That was how, at the age of sixteen, I met the man who made me. His face was owlish, his hair salt-and-pepper. He had the build of a banyan; he dwarfed Ma who sat next to him.

Some guests started to clap their hands to their thighs. All their bangles jingled.

Ma swept an arm my way and said to my father, “Your son. A Mathur obviously.”

Laughter spilled from everyone’s mouths. And some food.

The conversations around us resumed. Ma kept shaking her head to brush aside the two locks of hair that kept falling onto her forehead. He blushed when he tucked them behind her ear, and my neck went hot.

After dinner, an aunt took me up the stairs and to my father. He was sitting on my mother’s bed. I clasped my hands and stood before him with my head bowed.

“Ay-hay, look at him,” she said, “feeling nervous to meet Daddy. That’s so cute.”

She laughed and clapped the back of my head. She closed the door as she left.

“You’re not to call me that,” my father said.

My throat ached. I wanted to gulp down a bottle of water.

“No Daddy-Papa business. You’ll call me Pita-jee,” he said. “Now come here.”

He held my head in cupped palms. He thumbed my eyebrows, ran a knuckle down my cheek, turned me around, placed his palm on my back, turned me again. He studied me slowly, head to toe, until his little lashes met.

“Are you asleep?” I asked. “Should I go?”

He laughed with his eyes closed and his shoulders shook. He picked me up, his sixteen-year-old, and put me on his lap. Four of his shirt buttons were open. He smelled of something pleasant and foreign. He pressed his cracked lips to my forehead, then opened his eyes. They were hazel like mine. The edges of his mouth curved downward.

Downstairs, Ma and our visitors sang bhajans as they cleaned the backyard and the kitchen, their voices punctuated by the dull clang of metal pans, by the mop’s wet slurp on the floor.

It was a mild October day so my uniform didn’t reek of dried perspiration; that felt like a small consolation. I leaned into my father and wrapped tentative hands around his shoulders. A hug would bring our reunion to its end, I thought, and he’d let me slip off his lap and go back to my room.

Instead, he pressed me to himself. He smothered my face against the wiry hair on his chest. His stubble scraped my forehead. He scrubbed my arms ferociously. His throat, as he cleared it, rumbled against my forehead. His embrace felt less like an act of affection, more like a punishment. Punishment for what I’d done.

I panicked and pressed my forearms to his chest and tried to place some distance between my body and his. When his tight grip frustrated my attempts, I raised my head and bit his ear.

Excerpted from The Sea Elephants by Shastri Akella. Copyright © 2023 by Shastri Akella. Used by permission of Flatiron Books, an imprint of Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC. All Rights Reserved.