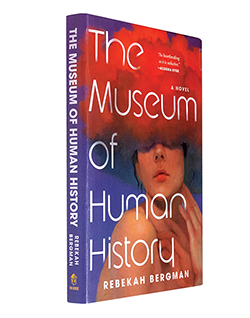

Rebekah Bergman, whose debut novel, The Museum of Human History, will be published by Tin House in August, introduced by Tiffany Tsao, author of the novel The Majesties, published by Atria Books in 2020. (Credit: Bergman: Phoebe Neel; Tsao: Leah Diprose)

![]()

Reading The Museum of Human History felt like listening to a great harmonic hum. After I finished it I found the hum lingering in my ears. Its echo continued for days. Bergman’s novel is made up of individual stories, told delicately and vividly, that the reader gradually realizes are the components of a larger narrative. Much like the notes of a chord. Much like the threads of a tapestry. Much like the separate exhibits in a museum. A girl’s twin sister falls into a deep slumber and ceases aging. A woman with terminal cancer drives cross-country with her partner to fulfill a dying wish. Ancient human remains are unearthed on an island. In another country, blue corpses lie in open graves. And a breakthrough in youth-preserving technology casts an ominous shadow over everything. These are just some of the intertwined narratives in the novel. Collectively they raise perennial questions of human existence: What is the balance between paying homage to the past and being consumed by it? Between preserving life and living it? Is pain—and the memory of pain—a blessing or a curse?

The Museum of Human History has a distinctively sci-fi feel: Biotech and anti-aging technology play a large role in the novel. Yet the epigraph is drawn from “Little Brier-Rose,” the Grimm brothers’ version of the Sleeping Beauty narrative. Could you tell us a bit about the novel’s blending of science and fairy tale—two things that some people might consider antithetical?

As different as they are, fairy tales and science fascinate me for similar reasons. I began my research for this book with geology. There were a few geological facts that were rattling around in my brain: the speed at which tectonic plates can move—as fast as our fingernails grow—and analogies meant to show just how small human existence is when considered on the scale of our planet’s history. Researching the fossil record made me consider all the life that was not preserved and all the history that is unknown and lost to time. I kept circling around this concept, as did my characters. At some point while drafting, I realized that I was drawing from the story of Little Brier-Rose, so I reread the brothers Grimm and other versions of folk and fairy tales and scholarship about them. You mentioned the book’s epigraph, and there was a different quote from the brothers Grimm that I considered using. The quote was from the preface to the second edition of their fairy tales. I loved it because it seemed to argue that fairy tales are also a kind of fossil record. Wilhelm Grimm wrote: “[W]e discovered that nothing was left of all those things that had flourished in earlier times; even the memory of them was nearly gone except for some songs, a few books, legends, and these innocent household tales.” So in a novel preoccupied with the weight of forgetting and of being forgotten, both geology and fairy tales offered me ways of examining what remains of the past.

There is much interplay in your book between the desire to forget and the refusal to do so. Did this affect the way you chose to structure the novel?

The novel has a large cast of characters. Each of them has their own past, and each winds up struggling with the burden of memory. The structure was a real challenge for me because I needed to strike the right balance between the individual threads and the way they weave together toward a whole. Structurally each character takes a central role in one main plotline and a peripheral role in others. I hope that choice allows the reader to see the tenuous grasp any one of us has over memory. Recollections are contested, fragile, and impermanent. What one person tries to forget or forgets despite their best efforts, someone else remembers—perhaps with a key difference or omission. One person’s buried secrets are uncovered, but the mere act of uncovering them changes them irreparably. Less to do with structure, but on a personal level, these themes of memory have a lot to do with my own memories of my grandfather. He survived the Holocaust and later in life was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Before his illness he very rarely spoke to me of the horrors of his past, but his disease made him lose track of the present and relive the worst nightmares of it. Seeing this had a tremendous effect on me and shaped a lot of the novel.

Would you say that writing this novel changed you?

I do think writing this novel changed me. It certainly changed how I think of my identity as a writer. Before embarking on this project, I wrote only short stories—often very short stories. Eight years later I no longer feel as intimidated as I once did by longer projects, larger word counts, or longer timelines. I think it’s possible, too, that I had to change in order to write the book. I began the first draft shortly after finishing grad school when I was in my mid-twenties. When I finally wrote my way to its true ending, a lot had changed for me. I had recently had a baby, and that experience impacted how I thought about and experienced the book’s main themes—time, memory, sleep!

How did you know you had finally written the book’s “true” ending?

At a few points the only thing I really knew was that I had gone as far as I could on my own. I could always tell when this was happening because the more I tried pushing against whatever problem I was struggling to solve, the more things would fall apart in my hands. I was very lucky that at each of these moments I found people willing and able to help me find my way again. When it came to the ending, my editor’s guidance was instrumental. The novel has a lot of heaviness: sadness, heartbreak, disappointment. In one conversation about the ending, my editor said she felt that the book could use another moment of buoyancy. I won’t say too much about the final scene, but it was that word buoyancy that set me on a path toward it. There’s the Aristotle quote about how endings should be “surprising yet inevitable.” And I definitely surprised myself because I wrote the last scene in a single sitting. That almost never happens to me. When I had finished, it felt like the puzzle pieces I’d been forcing together had shifted the slightest bit, which allowed them to lock into place. I also didn’t have to think about it too hard; it simply felt right in a way that it hadn’t before.

An excerpt from “A decade into Maeve’s sleep” from The Museum of Human History

Every Thursday, Lionel trimmed Maeve’s fingernails and toenails. He had opted to keep her hair long. He washed and combed it and let it spill out below her head to fall onto the floor.

He mostly ignored the protest signs on his neighbors’ lawns and the new petition about his daughter and her followers. He turned Maeve’s body every eight to ten hours so that she would not develop bedsores. Each time he did so, he knocked softly against the nightstand in a set of three to create an old rhythm: quick, quick, long; quick, quick, long. Like a horse’s gallop. He thought of Evangeline coming home when he did this. He believed he was only remembering the past and not, also, imagining any hoped-for future of her return.

![]()

Evangeline had been following the story of her twin sister. She had learned all about the complaints in the neighborhood along with the newest miracle of her followers.

There had been, by the accounts, three miracles.

In the beginning, it was simply that Maeve had kept breathing. Almost a year after the accident, there were hundreds of moths born beside her in an instant.

When those two events occurred, Evangeline had still been living in the house. But now, now that she had spent more of her life without her twin, there was a new miracle.

Maeve had fallen into her sleeping state at the age of eight. By eighteen, she should have undergone a complete metamorphosis from child to teen. But though her hair and nails kept growing, the rest of her remained untouched by time.

The procedure to end aging had been a disaster and thousands were left with broken promises, broken lives, broken memories. But here was her sister, asleep and unaged; preserved and remembering, somehow still, to breathe.

Once this came out, the Congregants’ numbers ballooned.

What did Lionel make of it? A reporter asked him this in the latest article that Evangeline had found. “Is it a miracle?”

Lionel was said to have smiled and shrugged and told the reporter, “I couldn’t say.”

Evangeline could picture her father precisely in that scene—that shrug, that smile, that noncommittal response.

She had always struggled to find the right words to describe him. The indecisive man who had decided one day to stop raising her.

Maybe nothing could describe him as concisely and accurately as his two passions: astrophysics and insects.

He was incapable of living in and understanding the human world.

![]()

Lionel used to think that caring for a sleeping child for a decade had changed him fundamentally. He thought it had fully worn down the hard outer shell that had been his optimism, his old eagerness to believe that the best possible scenario was also the most likely.

Was it a miracle? the reporter had asked him.

He couldn’t say. He really could not.

There were, he felt, several equally likely explanations. He had believed that he was capable of holding all these possibilities in his mind and feeling a compassionate nonattachment. He had thought Maeve had taught him this.

For instance: It might be a miracle. And it might not be.

Maeve might wake up. And she might keep sleeping.

Naomi may have intended to kill herself. And she may have drowned by accident.

Evangeline might yet come home. And she might stay away.

But then Evangeline had sent him a letter.

It was her final question on the list of questions that pinched at him, shaking his confidence in his own agnosticism.

When he thought of all the possible answers and outcomes, he liked to imagine each as a string—in the cosmic sense, like string theory—one-dimensional, theoretical. But at the other end of them—he could not help it now, since reading her letter—he had started to picture some greater power, pulling and spinning those strings.

And what was that if not, after everything, the highest form of optimism: faith?

Excerpted from The Museum of Human History by Rebekah Bergman. Published with permission of Tin House. Copyright © 2023 by Rebekah Bergman.