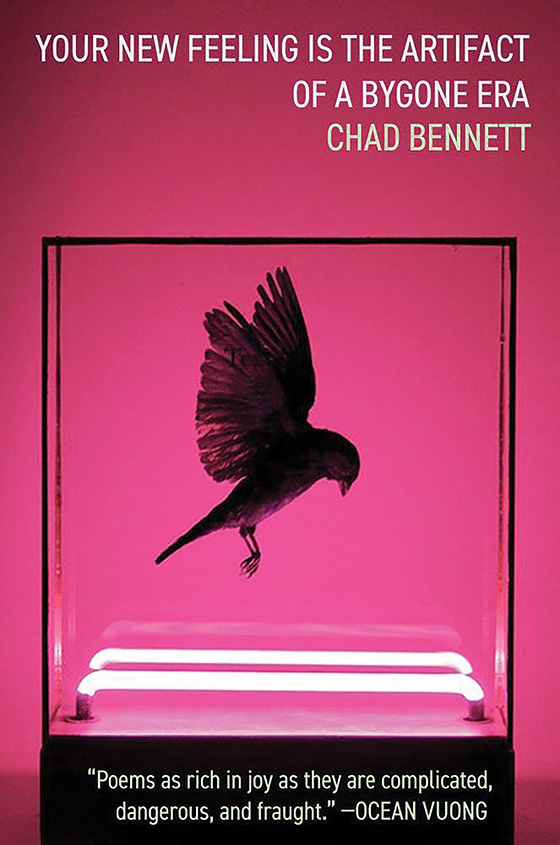

Chad Bennett

Your New Feeling Is the Artifact of a Bygone Era

Sarabande Books

(Kathryn A. Morton Prize in Poetry)

What we have is small

and strange. But true.

—from “Trick”

How it began: The book emerged from the off-kilter personal experience of ending a long-term relationship and coming out as a gay man at a relatively late age. It’s a book of love poems, and being in and out of love accordingly compelled most of the poems into being.

As I wrote I was becoming aware of not wanting to write mere love poems, or perhaps rather of wanting to claim the value of that mereness. I was understanding poetry as a powerful form of knowing, one motivated by love and by love’s desire to name itself and its world. I was finding myself wanting to sing about and assert the joy and the grandeur and the potential of the self in love, the self at its most radically capacious. And I was also trying to understand and to live within the damage—to the self, to others—one’s love inevitably causes.

Inspiration: Three loved volumes that I first read many years ago made me want, in earnest, to be a poet and to someday make a book of poems: D. A. Powell’s Tea (Wesleyan University Press, 1998), Carl Phillips’s Cortège (Graywolf Press, 1995), and Frank Bidart’s Desire (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997).

Each individual poem, too, has its own set of inspirations: The book includes a six-page set of “Annotations” that names the idiosyncratic archive of voices—ranging from Emily Dickinson to Francis Bacon to Joe Brainard to Cy Twombly to Arthur Russell to Bernadette Mayer to Frank Ocean—that inspire specific poems. I won’t rehash that list here. But queer histories, and the sustaining, communal repertoire built out of the detritus and ephemera of those histories, set many of these poems in motion.

Influences: Not a poet or artist, but a formative entry to file under “influences”: My dad is—or was, he recently retired—a garbage man, and growing up, I used to work for him in the summer. This might sound hokey, but I think that seeing, each day, streets of trash cans lined up and moving down them—emptying one container after another into the truck by hand, counting them off—shaped my understanding of rhythm, of form, of pattern and embodiment. My dad’s route appeared like an ideal grid that we moved through, but each iteration of it contained endless variation. Also the content: Picking up people’s trash is instructive! You learn shit, seeing what people throw away. I still have dreams about it.

Poetic influences? Given more space, this would be a very long and mutable list. Here, I’ll say that I am always returning to the erotics of style both theorized and enacted in the writings of Roland Barthes, to the frankness and acuity of James Schuyler, to the formal thinking—or thinking form—of Gwendolyn Brooks, and to the radical play and impossible ambition of Gertrude Stein.

Writer’s block remedy: There’s a Jack Spicer epistolary poem in which he affirms “THAT POETRY ALONE CAN LOVE POETRY” and “THAT POEMS CRY OUT TO EACH OTHER FROM A GREAT DISTANCE.” When my writing gets stuck, I start reading and keep my ears perked for those poems that are calling out to my poems from across the distance.

Advice: I’m somewhat old for a debut poet, and my circuitous path to publication—and through life, for that matter—often seems to me a sort of cautionary tale. All of which is to say: I’m wary of offering advice. But, for whatever it’s worth, I have found it liberating to embrace my slowness, my shyness, and to let the poems unfold in their own time and in their own ways rather than according to the pressures that structure the poetry world at its worst. I’m still learning this and find it useful to remind myself that, for me, anything that makes the poems feel more like products than part of an eccentric, vitalizing process is against a life in poetry. Anything that would reduce the deliciously noninstrumental pleasures and powers of the queer practice of poetry is against a life in poetry.

Finding time to write: Writing, for me, involves the sort of close attention that can be a lot like spacing out; it involves long stretches of reading; it involves getting absorbed in fun, finicky formal exercises that might take up hours and produce only a few bad lines. All of which is to say: There’s never enough time for the large gaps of loafing and play that poetry requires. But I try to stay alert to the bits of song that zoom through my head, and to get them down somehow—they seem to make time dilate. Just a phrase on paper can form a snag in the day’s fabric, something to pull on and unravel into a poem, a sort of temporary stay against any demand for a putatively more productive use of my time.

Putting the book together: The book’s central poem, “Silver Springs,” thinks through the musical fade-out. The fade-out interests me because it ends without ending. It carves out an ongoing time (and space) somehow adjacent to the song; we can’t necessarily inhabit it anymore, but we can’t forget it, either. This technique resonated with my desire to write about relationships that end but don’t end, with histories that step in and out of present moments, with all of the artifacts of bygone eras that inform my and my culture’s seemingly new feelings. Starting from there, then, the book’s structure—its sections and the placement of poems within those sections—became chiasmic, or mirroring, fading in and fading out. Within this frame I thought a lot about montage: the cut from one poem to the next and the new meanings that emerge in those cuts. (These are also all good Generation X skills, honed while obsessively crafting mixtapes.)

What’s next: These days? Mostly just trying to hold on to some sense of inner quiet. But in the midst of that, three projects are vying for whatever attention I can muster right now. I’m writing new poems. I’m developing a critical study of the poetics of queer awkwardness. And I’m also trying to write a book—part poetic essay, part memoir, part theory—about the nourishing but often fraught relationship between women and gay men. Our culture’s vocabulary for that relationship (fag hag, gay accessory, beard) is impossibly impoverished. In writing about ending a long, intimate partnership and its off-kilter transition into some other potential way of being together, I’m trying to do justice to the affective space of this relationship and to situate it within a broader history of relationships between women and gay men both like and unlike ours.

Age: 44.

Residence: Austin, Texas.

Job: I am an associate professor in the English department at the University of Texas in Austin; my teaching and research focus on contemporary poetry and poetics and queer studies.

Time spent writing the book: Most of the book was written during a weird six-year period beginning with my move to Austin. But it includes revisions of less recent poems, too; the oldest was first drafted about twenty years ago. So, six years? Nearly twenty years? The former is probably more accurate, but the latter feels to me more true.

Time spent finding a home for it: It was surprisingly fast: five months. Years ago, after previous manuscripts had repeatedly come close but failed to find a publisher, I started to feel like worrying about publication was keeping me from moving around in my writing, and that I was handing over the main pleasures I took in poetry—its ability to make its own little worlds and to foster queer connections—to other authorizing forces. So I took about a decade off from submitting my work, wanting to slow down and establish a poetic practice that existed, at least as much as possible, apart from the churn of Submittable or any sense of needing to produce or to publish for the sake of being published. The poems in Your New Feeling Is the Artifact of a Bygone Era came out of that renewed sense of practice, and of poetry as a way of being in the world. When it eventually made sense to seek readers for this work, I was incredibly lucky to have Ocean Vuong select the collection for the good folks at Sarabande Books and its Kathryn A. Morton Prize in Poetry.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: It’s difficult to name just a few, but I’ve been especially taken by Tommye Blount’s Fantasia for the Man in Blue (Four Way Books), Benjamin Garcia’s Thrown in the Throat (Milkweed Editions), Stephanie Cawley’s My Heart but Not My Heart (Slope Editions), and Ricardo Alberto Maldonado’s The Life Assignment (Four Way Books). And I’ve loved having my book elevated by being in the stellar company of Sarabande’s 2020 debuts: All Heathens by Marianne Chan, Index of Haunted Houses by Adam O. Davis, and Hotel Almighty by Sarah J. Sloat.

Your New Feeling Is the Artifact of a Bygone Era by Chad Bennett

![]()

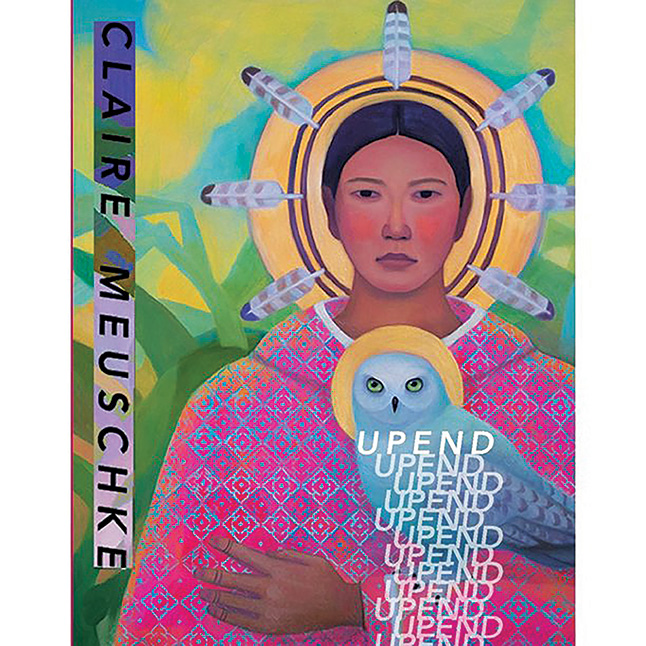

Claire Meuschke

Upend

Noemi Press

birds made homes out of trees and then we did

associated or dissociated

a figure is real

a number is literate

products like people

come with a number and a name

—from “figurative as literal”

How it began: Two events happened that coiled my mind toward writing the book: In 2012 my twin brother and I went to the National Archives at San Francisco in the hopes that we might find out the name and specific birthplace of our Alaska Native great-grandmother. Instead we were handed a forty-two-page immigration trial documentation of her son, our grandfather, who was half Chinese. He, along with hundreds of thousands of predominately Asian people, was incarcerated on Angel Island, in California, during the Chinese Exclusion Act when he was seventeen years old.

In 2014, I worked for the U.S. Forest Service in a New Mexico oil and gas–centered bust town. I was the only young woman who worked in the district, and I left because of increasingly threatening behavior from male coworkers, neighbors, and oil and gas workers.

It wasn’t until I started my MFA in poetry at the University of Arizona when I began to see these events as related—a trajectory of state-sanctioned violence. My great-grandmother lived and died in San Francisco around the turn of the century when the city was male-dominated, echoing recent gold depletion and California Native genocide. I obsessed over the U.S. concept of recreation, the corralling of beauty, and began to see what recreation conceals: genocide, the forced removal of Indigenous communities who lived and cared for what are now federal parks, and the incarceration and deportation of nonwhite immigrants or those suspected to be immigrants. I toiled over my love for nature, and the poems came out of this toiling.

Also, I attempted to address connections between the gold rush and the tech boom in the West. I wrote the book in the Southwest, supported generously by the land and people there, and never thought I would be able to afford to return to the Bay Area, the place where I was born, financially or emotionally. I can’t really, but I’m here. The layered complications of gentrification, outsider-ness, and belonging through time and place compelled me to write Upend.

Inspiration: I tried to catalogue my points of inspiration in the back of the book, but of course forgot and forget many of them. Here are some: the seemingly futile, lifetime task of recovering my ancestors; my twin brother, Gus Meuschke, and older sister, Nicole Meuschke, who both share the complicated relationship to family and belonging; paint color names (i.e. Sherwin-Williams and L’Oreal Paris nail polish); long walks with my dog, Mica; Josephine Foster singing Emily Dickinson poems; Big Thief; female vocalist and female-centered movie recommendations from, and general companionship with, my dear friend and linguistic-genius-poet, Paul Bisagni; Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas (Graywolf Press, 2017); CAConrad’s (soma)tic poetry rituals; Saidiya Hartman; old newspaper articles from the San Francisco Call; old, racist settler manuals; Taneum Bambrick and her collection, Vantage (American Poetry Review, 2019), and our friendship that aligned serendipitously while we wrote poems involving workplace discrimination and recreation.

Influences: Fred Moten for his revitalizing commitment to sound and language and his community; Alice Notley for her bold sensitivity and ability to cross thresholds; Hoa Nguyen for the power she distills from daily life; and Brandon Shimoda for his ruminations on global and local phenomena, surpassing time and space.

Writer’s block remedy: I allow for the words to stop. I absorb as much as I can—books, poems by friends, and audio readings. I record my dreams. I write letters. I focus on the material world and how I can better exist in it. I rearrange my furniture. I weed garden beds. I take on a cooking project. I look at poems I love and try to mimic them. I wonder how I was ever able to write a poem and doomspiral about my place and the poem’s place in the world, and then chastise myself for being so self-centered. I curse myself for not having chosen another art form or for not studying science. Eventually, the impulse to write comes back, but I’m open to the idea that one day I’ll have writer’s block, and it’ll last the rest of my life.

Advice: So much is up to chance: what’s happening in the world the day someone reads your manuscript and their associations to certain words and affinities. Try not to despair over recognition on a larger scale, and lean toward the select few who enjoy your work. Write for your own enjoyment and for your own lineages, friendships, obsessions, and daily survival. Recent recognition has given me many gifts and opportunities, but it simultaneously skews my sense of why I do this on a physiological, intellectual, and ritualistic level. For me, the idea of an audience can be draining. Try to enjoy the time of exploration and keep sight of the poet you wish to be.

Finding time to write: I’m fortunate to have a fellowship that allows me time to write, though I found out I can’t write well when I have so much time to worry about the future (in the most expensive, exclusive region of the United States). I need to tether my hours to the land and people around me, and the writing happens in fragments. The impossible conditions of making a living as a poet have conditioned me to write in the odd hours.

Putting the book together: For years I printed poems and shuffled them around my living room floor and taped them on walls. I looked at shape, form, context, and narrative energy versus narrative excess. I was lured by Bhanu Kapil’s gesture in her exquisite book Schizophrene (Nightboat Books, 2011) to disintegrate the manuscript and write it again from the remnants, but I realized it wasn’t that kind of project. I needed to keep the facts intact. I wanted the book to exist as an archive for myself to remind me of where I left off.

I thought the book might work best as a triptych or with sections that held an order related to color, afterimages, time, or place. However, the poems resisted any sort of linear narrative, categorization, or even a table of contents. My editor, Diana Arterian, generously helped me decide on which archival ephemera to stagger throughout the book. The paint swatches containing the word gold ended up filling the role of section breaks. In my earlier years of studying poetry, Anselm Berrigan introduced me to the phrase “elegant mess,” and that shaped and has shaped my approach to organization and writing. I’m a poet of excess, but I’m also stubbornly particular about how I want contextual sequence, appearance, sound, and space on the page to exist.

Upend has become a blueprint for future projects. I hope that my readers can experience the book from front to back if time and energy allow, but I also hope readers can glean something from opening to any page at random.

What’s next: I haven’t finished the project that Upend started. I’m a tacky poet of gimmicks, so the generative title for my new project is End Up, in which I write from the daily life of living in the Bay Area—the backdrop of Upend—where I can walk a few blocks to the cemetery in Oakland that holds my grandparents and simultaneously see Angel Island in the distance where my grandfather was incarcerated. There’s an archive in Eugene, Oregon, which has family letters between the missionaries who housed my great grandmother and her children in San Francisco Chinatown. I need to visit it to see if there are any offhanded mentions of my family in these letters.

I also want to continue a research thread started in Upend on the U.S. Forest Service and NASA’s collaboration on moon trees. I’d like to visit the trees and write about the erasure of the communities who lived on those sites.

I’m thinking about serpentine, as a rock and as a word. It emerges from oceanic floor through seismic activity. It’s not actually any singular thing, but it’s comprised of multiple minerals to create a snake-like appearance. I’m interested in how the quality (adjective) becomes a solid, symbolic rock (noun). As a mixed-race person, full of qualities and empty of singularity, I’m intrigued and slightly envious of its holistic acceptance as California’s state rock.

Mostly I’m enjoying not having a project and have been writing poems that I hope can stand alone. Soon I’ll look at them together and understand the weight of the task at hand.

Age: 30.

Residence: Oakland.

Job: Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and farmhand–farm assistant.

Time spent writing the book: I tried to write poems in 2012 on the back of reproduced pages of my grandfather’s immigration trial, but instead used them for grocery and to-do lists. When I worked for the U.S. Forest Service, I wrote a couple of Upend’s earliest poems discretely on some flash cards I kept next to my computer mouse. I didn’t seriously begin the project until I started my MFA in 2015. Even when it was accepted for publication three years later, I kept working on it. I’m still writing poems for this book, so it’s ongoing.

Time spent finding a home for it: In the second year of my MFA I sent the manuscript to presses I admire—Nightboat Books and Futurepoem—even though the manuscript didn’t feel ready. I was an adjunct the year following my MFA, and my mentor Farid Matuk told me he sent some of my poems to Carmen Giménez Smith to consider for Noemi Press. Carmen reached out to see my whole manuscript, and about half a year later, Noemi Press decided to publish it. The morning I found out I woke up from a gas-stove leak in my home. I was nauseous and disoriented, so it all felt very surreal when I read the e-mail. In short, I didn’t try very hard to publish and thought that I would be working on the manuscript for much longer. There’s a line in one of my poems in which the speaker says, “I don’t believe in luck,” but that’s not true for me. I’ve had so much luck and generosity thrown my way.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: I’m so behind, but I recommend wholeheartedly Jessica Q. Stark’s Savage Pageant (Birds LLC), Monica Sok’s A Nail the Evening Hangs On (Copper Canyon Press), Joy Priest’s Horsepower (University of Pittsburgh Press), and Benjamin Garcia’s Thrown in the Throat (Milkweed Editions).

Upend by Claire Meuschke