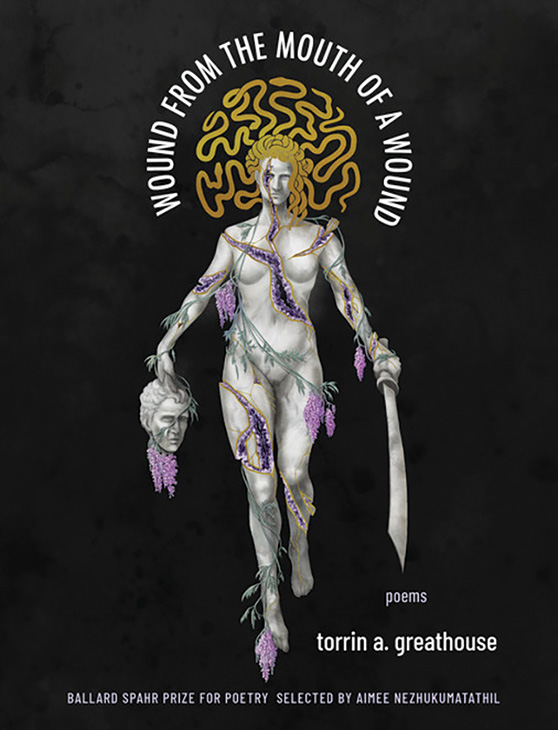

torrin a. greathouse

Wound From the Mouth of a Wound

Milkweed Editions

(Ballard Spahr Prize for Poetry)

...Misplaced chromosome.

Missing rib. Screw balded as a knuckle. First cell to

metastasize. Our language unable to speak my gender

out of disease...

—from “When My Gender Is First Named Disorder”

How it began: It was several things simultaneously: beginning hormone replacement therapy after coming out as trans; entering therapy for the first time in an attempt to process years of trauma; pursuing medical care for help with, and a diagnosis for, my progressive health issues; and the beginning of Trump’s presidency, when he began to enact executive orders and push for legal actions strategically stripping away the rights of trans and disabled people. This collection came out of the urge to document my realizations about the inextricable and interconnected nature of my trauma, disability, and transness, and to explore and critique their parallel medicalization.

Inspiration: This collection is largely working within the realm of memory, of trying to build a kind of fragmentary narrative. Still there are a fair number of poems with unusual inspirations: the wedding dress of an ex who assaulted me, my hatred for the casual use of the word lame, and the list of fifty preexisting conditions which could have excluded an individual from accessing the American Health Care Act of 2017 (the Republican’s plan for replacing the Obama-era Affordable Care Act). Probably my favorite among these plays on the trope of “dream where you wake up in class naked,” prompting the reader to imagine the violence this means for a body like mine, before taking the poem in a different direction entirely.

Influences: Kay Ulanday Barrett, whose work gave me permission to exist on the page with the fullness of my being as a disabled trans writer, and whose uncompromising voice still pushes me to allow more unmediated joy and rage into my work. sam sax, whose book Madness (Penguin Books, 2017) was invaluable in shaping the rhetorical approaches of the poems in this manuscript that press against legal statutes and the medical-industrial complex. Ocean Vuong, without whose work I never would have taught myself to break a line. And my dear friend and contemporary George Abraham, whose work continues to teach me and has its DNA inextricably woven up in the craft of this collection.

Writer’s block remedy: I often return to two sources when everything else within me has run dry: etymology and ekphrasis. Language is such a complex and unwieldy technology, capable of profound softness and unfathomable violence. I try in my poetics to be attentive to this potential, and returning to the origins of English words—or their absence of traceable lineage—is a deep comfort and inspiration. Likewise, I have found the ekphrastic mode deeply generative, the image presenting a kind of door through which the poem can step. Many of my poems, even those that are not ekphrastic, begin with an ekphrastic impulse—the push to pick a lock and move deeper into an image. I am particularly interested in the potential of poems that decenter the traditional, received art-object, applying the logic of the ekphrastic to objects that might otherwise be ignored.

Advice: Don’t underestimate the importance of titles—of the book and the poems. A title has the capacity to do an immense amount of heavy lifting. It is what calls a reader into the work; it can construct an entire world before they enter it and is the first frame of reference for it once they have left it. Make sure you are leaving the readers carrying some part of the book after they finish it.

Finding time to write: My writing process has never been a particularly regimented one. As a disabled person living with chronic pain and fatigue, the romantic writerly practice that was described to me so often when I first began my career has always felt wholly inaccessible. Instead, my process is an act of accrual. I hold concepts, lines, and images in my head, on sticky notes, in my phone notes, or on scraps of paper throughout the house. They remain detached and unstructured until they require form. Then, almost regardless of the situation, they demand presence on the page. I’ve written poems parked in the freeway’s emergency lane, scrawled them frantically on my arm in marker, and gotten lost on a bus having ridden far past my intended stop.

Putting the book together: As a triple Virgo, I was pretty neurotic about the final ordering of the collection. I started by color-coding every poem for their themes, whether they were part of certain sequences, and the image systems they used. Then I created a flowchart organizing the poems into affinity groups based on these categories. I was lucky enough, despite being housing-insecure and not having easy access to a printer at the time, to have a partner working at a local university who secretly printed the entire manuscript during their lunch break. This meant that, for my next step, I could paper one wall of the tiny room I was renting with the pages, pinning them up and reorganizing them over and over again, following a set of rules I had established around allowable patterns in their categories, as well as based upon the arc created by poems’ first and last lines, until a pattern emerged.

What’s next: I’ve been working on a new collection for my MFA thesis, exploring the politics of desire, desirability, and intimate violence, through the lenses of transness and disability.

Age: 26.

Residence: I live in Minneapolis, where I attend the MFA program at the University of Minnesota

Job: I’m balancing a couple different jobs and side-gigs. I teach writing studies at the University of Minnesota, as well as creative writing workshops through the Speakeasy Project. I also usually do consultation and editing work for other poets, but I’ve put that work on pause since the pandemic—it just feels wrong to advertise these services when I’m financially secure and so many others are struggling.

Time spent writing the book: From the first poems written for the collection—almost none of which are still included—to the final line edits, around four years.

Time spent finding a home for it: To be completely honest, I began submitting this collection long before it was ready. But I was so sure I wouldn’t live to the age I am now that waiting seemed impossible. I submitted the collection for just shy of three years, but it would not reach the version it is in now until around a year before acceptance.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: This is a tough question, only because of the quality of debuts that were released this year. A few personal standouts were George Abraham’s Birthright (Button Poetry), syan jay’s Bury Me in Thunder (Sundress Publications), Roy G. Guzmán’s Catrachos (Graywolf Press), Benjamin Garcia’s Thrown in the Throat (Milkweed Editions), and Jubi Arriola-Headley’s original kink (Sibling Rivalry Press).

Wound From the Mouth of a Wound by torrin a. greathouse

![]()

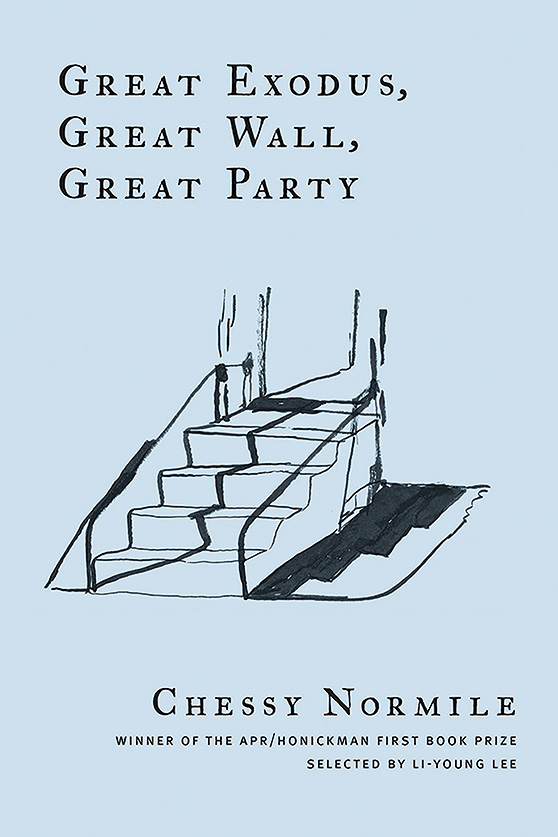

Chessy Normile

Great Exodus, Great Wall, Great Party

American Poetry Review

(APR/Honickman First Book Prize)

All the books on time

are pretty good.

—from “Ever”

How it began, time it took to write the book, putting the book together: I’ve combined these questions because I didn’t try to write a book, you know, so it’s hard to answer that one, but I think I can answer these all together in a kind of impassioned mess. I didn’t think of these poems as leading toward anything beyond their own conclusions. Each poem was different—some took years to finish, and some were done the same day they were written. I’m grateful I was required to turn in a manuscript for my MFA thesis because I was wary about leaving the world of individual poems and needed a push. I started by going through every poem I’d written over the past eight years or so and just made a fat stack of the ones that still interested me. Then I began working my way through the stack. It felt like making a stew that mostly required that I ignore it but occasionally required that I give it my full, undivided attention for five to eight straight hours. Then the stew would say, “Now shut the lid, I need another three weeks of uninterrupted stewing, but don’t forget about me, but don’t look at me.” And I’d have to obey even though it felt crazy and like I wasn’t in control at all—oh, so I guess it was actually a lot like writing a poem! The last step was that when I’d done all I could do on my own, I gave it to four people I trusted—Michael Adams, Sarah Matthes, Hedgie Choi, and Jackson Holbert—and they helped me so much. I felt scared, and they made me feel less scared, like I’d made something worth attending to and caring for. I don’t know, I just respect them all so much as poets, artists, thinkers, whatever you want to call the way they approach the world—and they helped me feel ready. After that, feeling a little more confident, I tried sharing the book with my sister and my then-boyfriend-now-husband, Thom. I remember when I gave it to Thom I thought, “This will be great, he’s gonna think I’m hilarious” because he writes such funny plays and I wanted to impress him with my comedy. But then he never brought it up! So finally I said, “Hey, no worries if you didn’t but…did you read the book?” And he was like, “Yeah. I did. It was really hard to read.” Turns out, he found the book devastatingly sad! This shocked me, so I called my sister and she said, “Yeah, Chessy, the book is really sad, how did you not know that? It’s funny, but it’s also really sad.” By the time I read Li-Young Lee’s introduction to the book and saw him saying the same thing, it was clear to me that the book is just inextricably both—funny and sad. I’m cool with that now, but it was something I had to come to terms with. The book had left my control, and I didn’t have a say in what it was in the end—not that I’d want one, given the option.

Inspiration: The people in my life combined with the agony/joy of being alive combined with music, reading, and being lost all the time. I’m also really inspired by my sister Nora’s art—she drew the steps on the cover of the book. As I wrote this I read books about time, color, consciousness, and the calendar; a lot of great poetry; a lot of the Bible; the gnostic gospels; and a lot of old books I’d never read before. Right now I’m rereading Seamus Heaney’s translation of the medieval Irish poem “Sweeney Astray.” Listen to this: “Think of my alarms, / my coming to earth / where the fox still / gnaws at the bones, // my wild career / as the wolf from the wood / goes tearing ahead / and I lift towards the mountain…” I mean…what to even do with that! I love poetry. If I let myself list the names of poets I love, it would be too frustrating because I’d never be able to name them all.

Influences: Marie Howe, Jeffrey McDaniel, Li-Young Lee, and Christianne Karefa-Johnson (DoNormaal). Jeff and Christie got me serious about poetry as a possible life. Their poems lit me up at eighteen and still do. Marie, I don’t even know what to say—what would I say about mud if I was a beaver? It’s the foundation of my life, lol. That’s what I’d say. Marie’s poetry and her attention to the world influence me deeply. And finally, Li-Young Lee! I’ve never met him, but I learned so much just from reading his introduction to my book I could hardly believe it. I sat on the edge of my bed and cried. Reading that gave me a sense of where I was meant to go next.

Writer’s block remedy: When I was in college, Heather Christle gave me some great advice that I hope she won’t mind my repeating. She said, “You can’t break your talent.” This did not, for the record, refer to my being especially talented—it just highlighted a fear she could tell I had about breaking out of what I thought I was able to do well. At the time, that was writing jokes that made people laugh. I was scared that if I tried something else, I’d forget how to do the thing I was good at. But it turns out we aren’t static like that. So I started pushing out in every direction, and the poems I was writing suddenly plummeted into this deeper space—and I carried the jokes there with me. It’s like Emily Dickinson wrote, “And hit a World, at every plunge, / And Finished knowing – then –” Then! At an impasse, I push myself into what’s unfamiliar.

Advice: This probably depends on which way you already lean, but in case you’re like me and think, “I should wait to assemble/publish a book until I’m writing the absolute best poems of my life, so I think I’ll hold off until I’m at least sixty and just keep chugging along, poem by poem, until I get really good at this,” then here is my advice: Let go! I don’t ever read a poet’s first book and think, “Wow, this is nothing compared to her last book, why did she publish this? She wasn’t ready.” It often helps to imagine what it would sound like to say the things you say to yourself to someone else. It can help you realize how much of a dick you’re being to yourself.

Finding time to write: I had three years given to me by the Michener Center for Writers, which was an incredible gift. Before that, I wrote on the train to and from work and sometimes on Post-it notes under my desk. I’d slip those into my bag and when I got home I’d stick them up on my wall and build a big poem like that at night. That’s actually how I wrote the first draft of the last poem in my book, “My Life So Far.” These days, because of the pandemic, I’m learning that I need to actively seek and create time alone for myself in order to write poems, which is new information.

What’s next: I’m just now getting back to writing poems. From when the book was finished to when it came out, I really struggled to write poems. I would write a line and then think, “What am I going to write on the next line?” It was a level of self-consciousness I’d never experienced before. As soon as the book came out though, that self-consciousness broke apart and I was able to write poems again. It feels like I jumped over a fence and these are the poems on the other side.

Age: 30.

Residence: Queens, New York.

Job: I do the packing and shipping for a ceramics studio. I guess it’s poetry-related in the sense that I’m surrounded by bells.

Time spent finding a home for the book: Two months. This was my first time sending the book out. My friend Sarah Matthes and I finished our books at the same time—she and Yuki Tanaka, another amazing poet, were the two other poets in my year at the Michener Center—and we thought, why not try this fancy route first and then, when we get rejected from all the prizes, we’ll try again, casting a broader net. But, lo! Both our books were taken. Hers comes out in April 2021 from Persea Books as winner of the Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize and it’s called Town Crier. It’s so good; I’m so excited for it to come out. I still find it hard to believe that my book was published, but I’m being careful right now not to say, “I simply can’t believe it, la tra la la” because, yes, it’s how I feel, but I’m not sure how useful that is.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Maiden (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press) by travis tate is so good. There are other great debuts, but if I list others you might not read Maiden. So just read Maiden.

Great Exodus, Great Wall, Great Party by Chessy Normile